Northern kelp forests take longer to recover from trawling

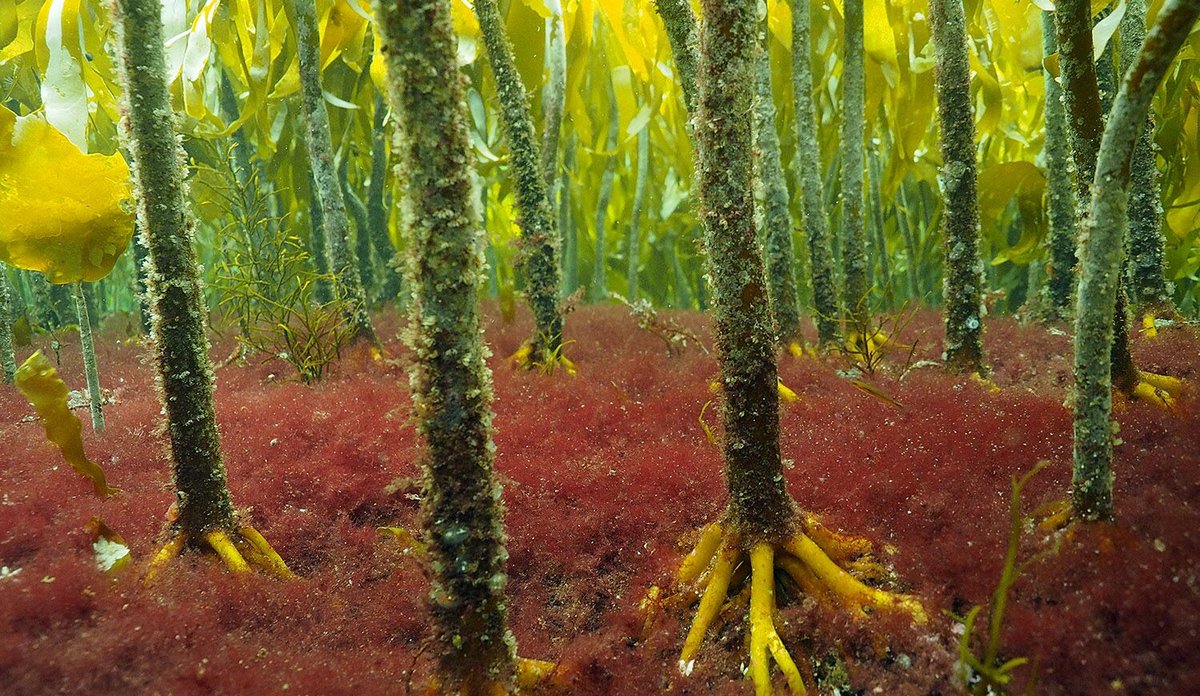

The kelp stems provide a home for red algae, moss animals, sea nettles, sponges and many other organisms that together constitute the whole kelp community.

Photo: Jonas ThormarPublished: 03.04.2018 Updated: 04.04.2018

“What we have seen is that the kelp forest with its whole community of organisms doesn’t quite recover to its state prior to harvesting. A four-year resting period is normal in other counties, but if we want the kelp communities to fully establish themselves between harvests, four years is too short in Nordland”, according to Henning Steen, a researcher at the Institute of Marine Research.

Fewer algae and animals in the kelp forests

For the past four years, scientists have been monitoring the kelp industry’s trial harvesting of kelp in the southern parts of Nordland. The researchers have looked at both how the kelp itself grows back and how life in the kelp forest recovers.

Kelp is currently harvested commercially along the Norwegian coast from Trøndelag and southwards, and the rules say that there must be a five-year interval between each harvest, to give the kelp a four-year rest. If kelp trawling is to start further north in Nordland, that interval will be insufficient, as it would not allow the kelp communities to fully recover between harvests. After kelp trawling, the kelp itself returns relatively quickly to its size and density before trawling, but researchers found that the diversity of algae and fauna on and between the kelp stems takes longer to recover.

Kelp forests create a three-dimensional environment that is probably an important nursery and feeding ground for many species of fish. The kelp stems provide a home for red algae, moss animals, sea nettles, sponges and many other organisms that together constitute the whole kelp community. Kelp communities provide important hiding places for small fish and crustaceans, which in turn are eaten by bigger fish.

“We can see clear impacts of trawling, even after a four-year resting period. The stems themselves are younger, and there is much less growing on them. The small kelp specimens in the undergrowth are also important, and four years after harvesting, they are still less abundant. A younger kelp forest is home to many of the same species, but in smaller quantities than in a virgin forest that has never been harvested”, explains Steen.

Valuable resources and ecosystems

In the past, a lot of the kelp in northern Norway was overgrazed by green sea urchins, but that species was not widely observed in the areas where the trial harvesting took place.

“The fact that the kelp forest has recovered and the green sea urchins are in retreat in this region increases the value of the resources and ecosystems. It is a very pleasing development that creates fresh opportunities. At the same time, these new kelp forests may be particularly vulnerable, and they need to be treated with greater care than the robust kelp forests further south”, says Steen.

Researchers are also concerned about the increase in red sea urchins in some of the areas studied. Red sea urchins mainly feed on the algae that live on the kelp stems, as well as grazing on the smaller kelp specimens in the undergrowth. Researchers therefore fear that the kelp forest will become less robust if you trawl in an area with lots of sea urchins.

“If trawling creates a worse habitat for the organisms that eat sea urchins, we may end up with even more sea urchins. That would worsen the growing conditions for the kelp and the kelp community.”

Conditions for fish and crustaceans

In Nordland, researchers were able to study the kelp forest prior to the first harvest, which means they have a very good picture of what harvesting does to the kelp community.

“We often lack ‘before’ data for the areas being studied, but here we were actually starting with a virgin forest. It is very valuable to have data on the situation before the first harvest.

Scientists are also studying the consequences of harvesting kelp on fish and crustaceans in both Nordland and the north of Trøndelag, and this work will continue in 2018.