Fishing increased around the lobster reserve

Since the creation of the lobster reserve in 2012, marine scientists have monitored the lobsters closely. Here Alf Ring Kleiven is doing experimental fishing in 2013.

Photo: Espen Bierud / Institute of Marine ResearchPublished: 21.01.2019

The marine protected area for lobsters in Tvedestrand is showing very good results for recruitment and the size of the lobsters that live inside it. That should also provide a surplus for the surrounding areas. In theory.

“There has been a general increase in the intensity of lobster fishing, but we are also seeing a psychological impact caused by the reserve. As you would expect the area surrounding the reserve to have improved as a fishing ground, more people want to fish there. The phenomenon is known as ‘fishing the line’, explains marine scientist Portia Nillos Kleiven.

Net result: fewer lobsters outside the reserve

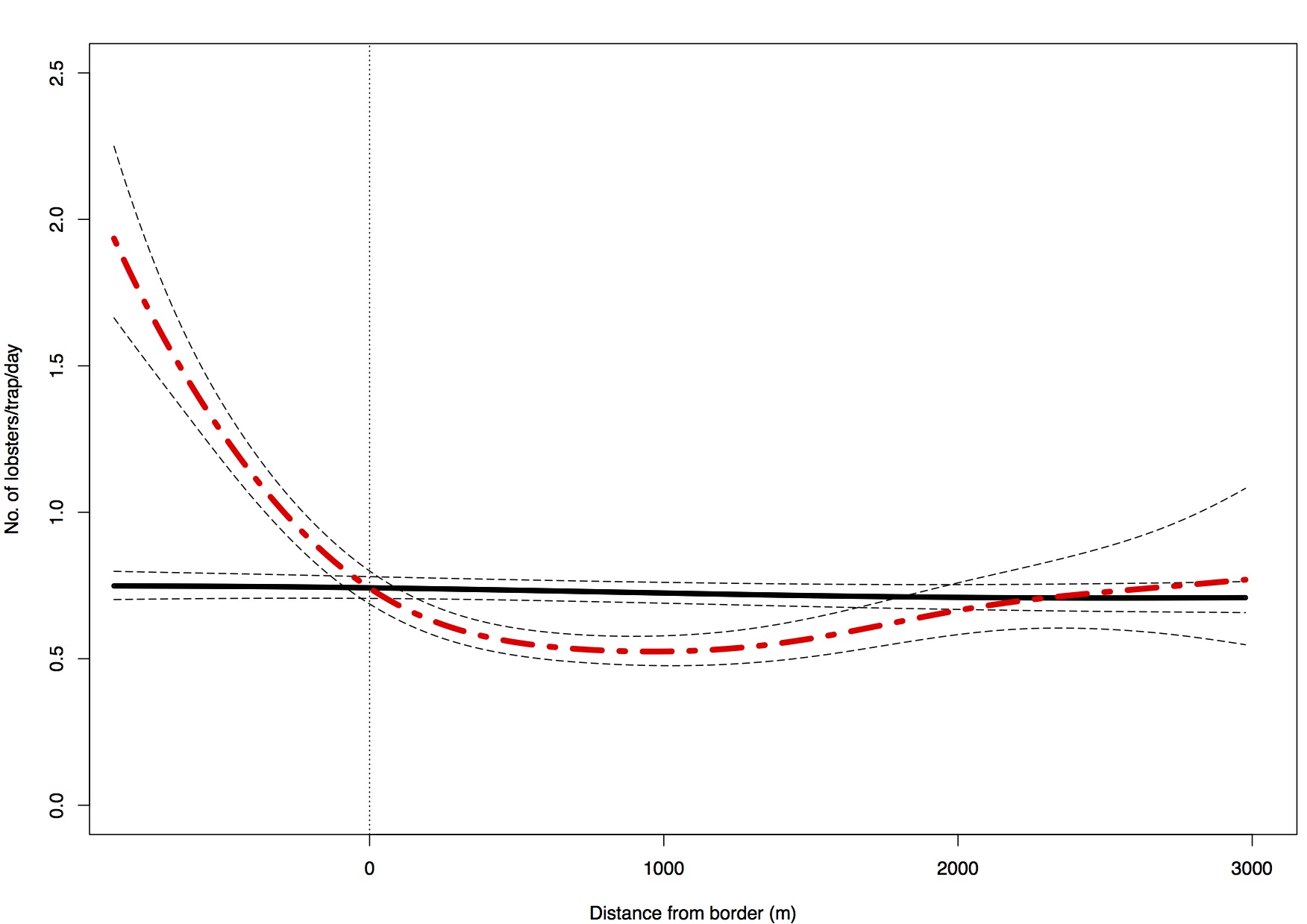

Her latest article in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences shows that the fishing pressure outside the reserve had doubled within four years of it being created. Over that same period, it tripled along the boundaries of the reserve. The net impact on the lobster population within 1.5 km of the boundaries was therefore negative.

“The reserve itself is beneficial to the lobsters that live there. Their number almost tripled over the same four-year period”, says Kleiven.

“Just outside the boundary, we see a decline in the population, and the situation improves as you move further away from the reserve.”

She believes the latest results show the need for a plan for the areas surrounding the reserve, if it is to have a positive impact beyond its own boundaries.

Can draw on lobsters from the reserve

If the fishing pressure continues to increase around the boundary, it is also possible to draw on the lobster surplus within the reserve.

“Empty habitats outside the boundary may attract lobsters from within the reserve. This may result in more lobsters being caught in the short term, but it will also negate the intended purpose of the reserve”, explains Portia Kleiven.

Studying the impact of reserves will become easier

Kleiven and her colleagues measured the changes in fishing pressure in and around the MPA by counting the number of lobster traps in the area before and after the establishment of the lobster reserve. Counting up to 3,000 pots spread across 52 square kilometres across the years is an arduous task.

In 2017 it became mandatory for people to sign up if they want to fish for lobsters, partly based on the IMR’s advice to the fisheries management.

“This will make it far easier to estimate catches and fishing pressure in the future. That puts us in a great position to learn more about how the authorities can optimise the design of lobster reserves.”

Reference

Portia N. Kleiven, Sigurd H. Espeland, Esben M. Olsen, Rene Abesamis, Even Moland og Alf Ring Kleiven . Fishing pressure impacts the abundance gradient of European lobsters across the borders of a newly established marine protected area. 287. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences

LINK: http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.2455