Mercury in fish at Fedje is not from submarine wreck

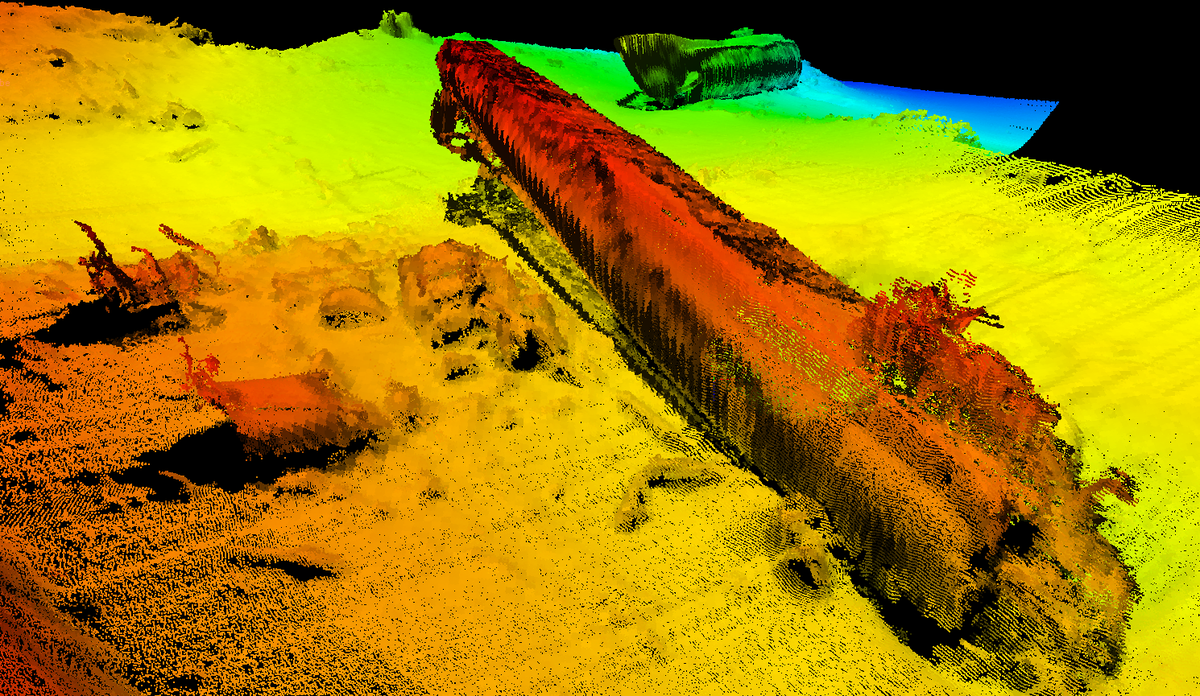

67 tonn med kvikksølv skal det ha vært om bordi U-864 som vart torpedert ved Fedje i 1945.

Photo: KystverketPublished: 23.07.2021

“The mercury found in fish at Fedje comes from the general pollution that is present in all of our coastal waters, and not from the wreck”, according to Sylvia Frantzen, a researcher at the Institute of Marine Research.

It’s tempting to think that fish swimming around the old submarine wreck at Fedje would be full of mercury. After all, the wrecked WWII submarine had 67 tonnes of mercury in its hull when it was torpedoed, much of which was spread out and now lies on the bottom of the sea around the wreck. Now researchers have found a way to show that while the fish admittedly contain some mercury, it doesn’t come from the submarine.

Fingerprinting mercury

By using an advanced method that is capable of distinguishing between mercury from different sources, scientists can find out whether the mercury detected comes from known sources of local contamination or from general pollution.

Different sources of mercury have different ratios of isotopes, which are atoms of the same element with different masses and hence different weights. By measuring the quantities of the various isotopes using advanced analytical instruments, they can read the “fingerprint” of the mercury in a sample and compare it with other samples.

Studies performed at Fedje show that tusk, a deep-sea fish that lives on the sea bottom around the wreck, contains the same kind of mercury as tusk caught in other places along the coast. It doesn’t have a special Fedje fingerprint, so the mercury it contains must have come from somewhere other than the submarine wreck.

“This is consistent with the fact that for many years we’ve found relatively little mercury in tusk at Fedje compared with at other places along the coast. If the mercury from the wreck had entered the food chain, you would expect to find a lot of mercury in the fish in the area. But we don’t find particularly high levels of mercury in neither liver nor fillet of fish caught here”, says Frantzen.

(Photo: Norwegian Coastal Administration)

Would have been worse in a fjord

Mercury is a highly toxic heavy metal, and excess quantities can affect brain function and development, particularly in foetuses and young children. That’s why Norwegian authorities monitor whether seafood contains more of it than it is safe for us to consume in the long run.

The mercury that has escaped from the submarine wreck and contaminated the surrounding sea floor is elemental mercury. As long as it is in this form it cannot be absorbed by living organisms. Nevertheless, many people are concerned about the mercury being converted into another, much more dangerous form of mercury: so-called methylmercury.

For this conversion to take place, there must be organic matter, combined with a low oxygen level, like there is in a deep, enclosed fjord, for example. This creates good conditions for microorganisms to convert elemental mercury into toxic methylmercury. In areas with open sea like off Fedje, less organic matter accumulates on the sea floor, and the water circulates freely.

“If this submarine had been in a fjord when it sank, the situation would be completely different”, explains Frantzen.

Tusk is representative of mercury levels in all fish

Tusk samples were applied for the study as there are lots of tusk around the wreck, and because tusk appear to be particularly useful for monitoring mercury levels in fish. Tusk are sedentary bottom dwelling fish that can come into contact with the mercury contaminated sediment. Moreover, as predatory fish they are high in the food chain, and they are susceptible to accumulating this toxic metal from the benthic organisms and other fish they eat.

Elsewhere, tusk have been found to contain higher levels of mercury than many other fish species, and the Norwegian Food Safety Authority has advised against eating tusk from fjords like Hardangerfjorden and Sognefjorden on account of the high mercury levels.

Samples taken previously of other commonly eaten fish species from the area around the submarine wreck contained lower mercury levels than those observed in tusk.

Mercury from far away

Mercury travels long distances in the atmosphere, so mercury that has, for instance, been emitted by a coal-fired power station in China may come down with rain or snow in Norway or in the Arctic. Mercury can also spread with water currents from densely populated areas and areas with industrial activities. In many places, long-range pollution is therefore the biggest source of mercury in the environment.

Scientists have also studied the fingerprints of the mercury in tusk caught elsewhere along the coast and in fjords. Except in the case of the tusk from Hardangerfjorden, where the mercury can be linked to local industrial emissions, the mercury in tusk cannot be linked to specific sources. The mercury in tusk caught further north, in the Norwegian Sea, had a slightly different fingerprint from the one in tusk caught in the coastal waters of the North Sea and Skagerrak.

“It appears that the further north you go, less of the mercury present comes from local sources, and more of it has been transported long distances”, says Frantzen.

You can read the whole scientific paper here