Haddock have an internal compass

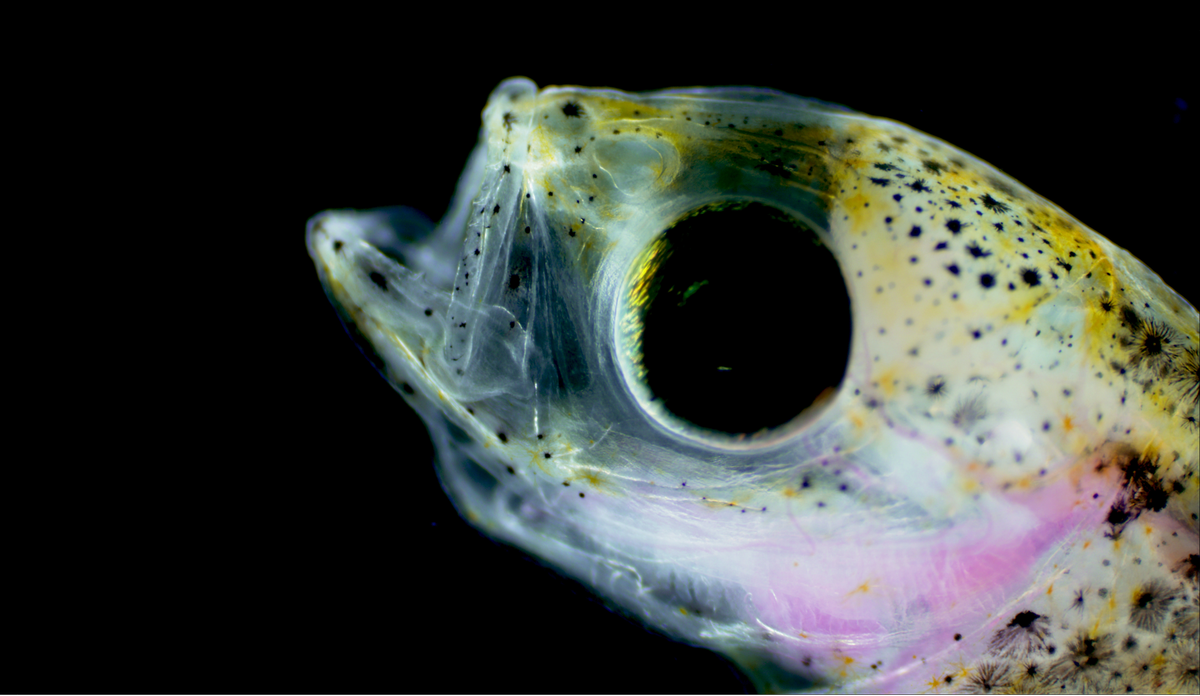

Haddock larvae as seen through a stereo microscope.

Photo: Alessandro Cresci / University of Miami / Institute of Marine ReseachPublished: 18.09.2019 Updated: 19.09.2019

In the Barents Sea and North Sea, haddock spawn far offshore on the continental slope. But the newly hatched larvae grow up in completely different places, much closer to the coast.

The larvae drift with the currents, but is that the whole story?

“By simulating the Earth’s magnetic field in a special tank, we have for the first time been able to show that haddock larvae don’t just hitch a ride with the current from A to B. They swim in a north-westerly direction with the help of an internal compass”, says marine scientist Alessandro Cresci.

A high-tech shed in the middle of nowhere

The “special tank” he’s referring to is the MagLab. On Huftarøy island in Austevoll, what may seem like a very ordinary shed stands in the middle of a field.

The “shed” has been specially built using only non-magnetic materials, right down to the smallest screw. It is also shielded against all kinds of noise. Inside, a water tank is surrounded by magnetic coils wound by several kilometres of wire.

“We can manipulate the direction of the magnetic field, rotating them 90 degrees at a time. In a figure of speaking, we can turn north into south, and so on”, explains Cresci.

Fish were studied in the tank and at sea

102 haddock larvae were left to swim by themselves in the tank while researchers documented the average swimming direction of every individual larvae.

Overall, the group of fish followed a mean course northwest, 319 degrees.

“We also observed 59 haddock larvae in a see-through chamber that was allowed to drift freely at sea. These larvae also headed northwest on a course of 313 degrees,” says Cresci.

Allows the larvae to cross the Norwegian Trench

“Why do you think that the haddock follow precisely this course?”

“If the haddock just drifted with the currents, we believe that they would end up more spread out than they actually do. Their swimming direction helps to counteract that tendency,” he explains.

“In the North Sea, the haddock might be carried along the Norwegian Trench by the coastal current and be spread out outside the North Sea. Using their internal compass to follow a north-westerly course, may be what enables the larvae to get across to the western side of the trench.

This is something that IMR scientists will investigate further.

Important information for fish stock monitoring

When marine scientists monitor a fish stock in order to provide advice on questions such as how much can be safely harvested, the drift of fish larvae is one of many things that they model.

“Both currents and fish behaviour determine where the larvae end up”, says Cresci.

Reference

Cresci, Alessandro, Claire B. Paris, Matthew A. Foretich, Caroline M. Durif, Steven Shema, C. J. E. O’Brien, Frode B. Vikebø, Anne-Berit Skiftesvik, and Howard I. Browman. "Atlantic haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus) larvae have a magnetic compass that guides their orientation." iScience (2019). LENKE: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2019.09.001