How little of the delousing agent is needed before juvenile lobsters develop ''arthritis''?

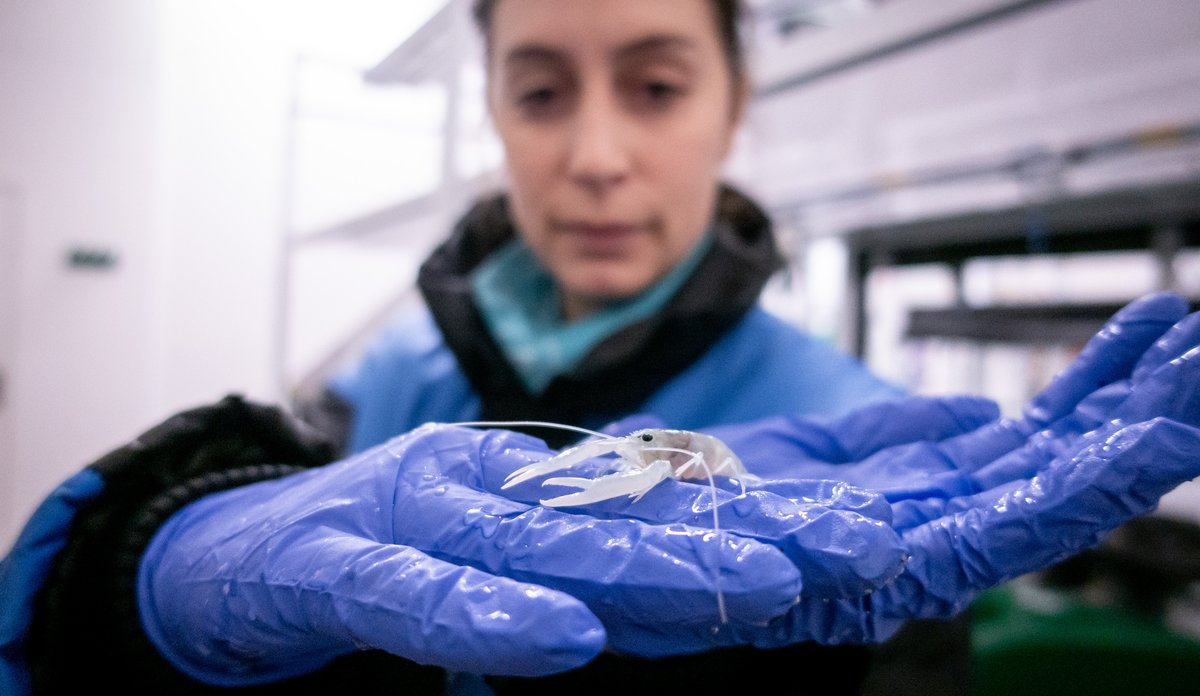

Juvenile lobsters are shelter seekers - they are never found in the wild. This one is hatched in the lab. Here with PhD-student Rosa Escobar Lux.

Photo: Erlend A. Lorentzen / Institute of Marine Research

After plenty of rounds, specially designed software will analyze the lobsters' activity.

Photo: Erlend A. Lorentzen / Havforskningsinstituttet

Four doses, including the control, are given to different lobsters.

Photo: Erlend A. Lorentzen / Institute of Marine Research

Rosa Escobar Lux is setting up the lanes the lobsters must navigate.

Photo: Erlend A. Lorentzen / Institute of Marine Research

This lobster has died while moulting, which can occur when teflubenzuron stops the formation of chitin, the principal component of the exoskeleton of crustaceans.

Photo: Erlend A. Lorentzen / Institute of Marine ResearchPublished: 13.02.2020 Updated: 06.08.2021

Teflubenzuron is added to the feed of farmed salmon in order to eliminate sea lice. The delousing agent then ends up on the seabed in waste feed and salmon faeces, where it may be consumed by other animals.

Die when moulting

“Teflubenzuron works by preventing shell formation in crustaceans. That affects sea lice, but also lobsters”, explains PhD-student Rosa Escobar Lux.

Researchers know that lobsters may die when moulting after being exposed to high doses of teflubenzuron. Now they want to know more about what happens to the lobsters that don’t die.

Struggle to find shelter

“In previous experiments, juvenile lobsters fed teflubenzuron developed stiff joints and antennae. They struggled to find shelter, which made them vulnerable to predators”, says Escobar Lux.

She is standing beside four oblong tanks with lobsters at one end and shelters at the other. A camera hangs above the tanks.

“In this experiment, we’re trying to pinpoint what amount of the delousing agent is needed before the arthritis like condition occurs and causes problems.

Do a weekly “obstacle course”

Four groups of lobsters must navigate the same course each week for several months. Three of the groups receive a diet containing varying amounts of delousing agent, while the control group receives normal feed pellets.

“We film their behaviour and analyse it objectively using dedicated software. The lobsters receiving the highest dose, are visibly affected and struggle to find their feet”, explains Escobar Lux.

A few have died and have been eliminated from the experiment.

Don’t know where they live

The doses of teflubenzuron used in the lab experiments are comparable to the quantities found on the seabed under fish farms. However, the researchers cannot say whether this chemical represents a risk to juvenile lobsters outside the lab.

That is because they can’t find juvenile lobsters in the wild – the ones in the experiment have been hatched in the lab.

Same effect

“We know little about where and how they live. But we must assume that teflubenzuron has the same effect on their bodies”, says Escobar Lux.

The researchers now hope to get enough data to estimate the quantity of teflubenzuron that is harmful to juvenile lobsters, both in the short and long term.

The results of the experiment will be taken into account in the overall risk assessment made by the Institute of Marine Research on delousing agent’s impact on species other than salmon and lice. See the 2019 risk assessment for Norwegian aquaculture.

(Experiments involving animals at the IMR must pass a strict assessment that involves weighing up their downsides against their benefits. In this case, the aim is to build up knowledge that may benefit the ecosystem.)