Sea monsters – and the natural explanations for them

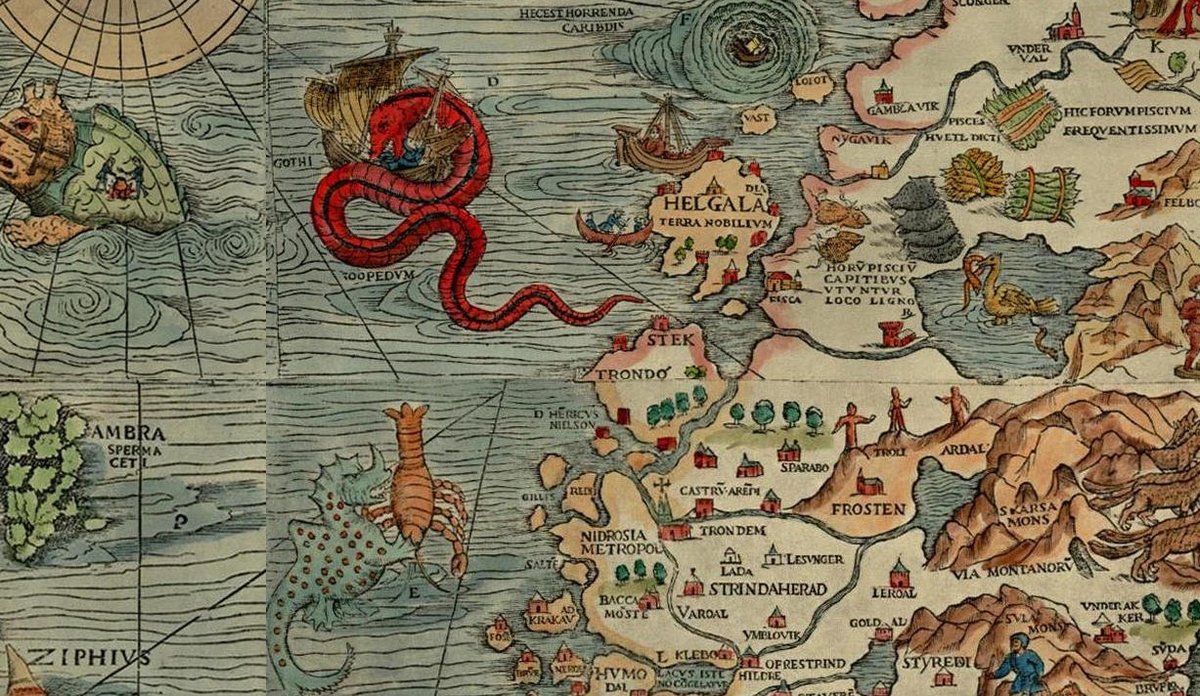

A sea monster off the coast of Helgeland on the old nautical chart Carta marina from the 16th century.

Photo: Carta marina by cartographer Olaus MagnusPublished: 20.04.2021 Updated: 28.05.2021

“When a giant squid washes ashore, it can set anyone’s imagination racing. A rotting whale carcass that remains afloat can look strange and grotesque, as there is loads of muscle tissue without any skin. It looks genuinely frightening.”

Those are the words of Gro I. van der Meeren, a multi-talented marine scientist with a longstanding interest in sea monsters.

“But for biologists, monsters don’t exist. There are just really exciting animals and phenomena”, she says.

Chinese whispers played over the centuries

“The Leviathan, the Midgard Serpent and the Kraken. Many of the world’s sea monsters are the result of a game of Chinese whispers that has lasted for centuries”, according to van der Meeren.

“Historically, many ocean phenomena were first described by people whose only knowledge of the sea was what they could see from the coast or from their boats”, she says.

“Their descriptions were then interpreted by land-lubbers educated by priests during the Age of Enlightenment. Those interpretations then informed more recent authors and historians.”

Humans need explanations

In van der Meeren’s opinion, one important reason for the existence of legends about sea monsters is the need of humans to explain why so many lives are lost and so many boats disappear at sea.

“Particularly in the North Sea and North Atlantic, the seas can be ferocious. We now know about gigantic waves that oceanographers didn’t believe existed just twenty years ago. If the wind and currents combine in the right way, they can produce ‘freak’ waves out of nothing, big enough to destroy the windows on oil platforms”, she says.

“So the ocean itself can help to explain some of the strange observations.” That’s how the game of Chinese whispers starts. Someone comes home and tells about their experiences, their story is lapped up by the Age of Enlightenment’s compilers of information, and in due course writers and authors draw on that material. Interpretations of interpretations can become highly imaginative.

The Kraken was the “good” monster

The Kraken is perhaps the most archetypal sea monster of them all. But it is also a slightly different kind of monster, at least in Norway.

“The Kraken was a good omen. When fishermen saw signs of the Kraken being in the vicinity, they were pleased. It meant they would get a good catch. The Kraken’s size and power made it a sea monster, but it was good for fishermen”, says van der Meeren.

The Kraken was described in detail by Erik Pontoppidan, an 18th century bishop from Bergen. For fishermen, signs of the Kraken included the water in their fishing grounds suddenly being just a few fathoms deep, the sea turning brown and a bad smell.

“That meant the Kraken had come up off the sea floor and was heading towards the surface with lots of fish”, says van der Meeren.

Signs of spring bloom and spawning

The phenomenon observed by the fishermen may have a more natural explanation. The water may simply have become “shallow” because there were dense shoals of fish high up the water column.

“We know that sometimes it’s impossible to lower your fishing gear because the fish are so densely packed below the boat. That’s often caused by juvenile saithe. The change in the colour of the water may be due to the spring bloom. This often occurs around the time of the spawning season for several large fish stocks”, says van der Meeren.

During the spring bloom, enormous quantities of plankton are produced in a very short space of time, and large numbers of fish gather at their spawning grounds to feast on the plankton.

“I suspect that Pontoppidan used words like ‘monster’ to refer to phenomena that he couldn’t explain based on his faith – but that doesn’t mean he thought they were dangerous. In the Middle Ages and Age of Enlightenment, the connotations of the term monster were probably slightly different from what they are today”, she says.

Became a giant squid and gained a bad reputation

However, in due course the reputation of the Kraken took a turn for the worse.

“The dangerous Kraken monster is a British invention, dreamt up by Sir Walter Scott and built on by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, who wrote sonnets about the Kraken”, says van der Meeren.

Around the same time the Kraken also became mixed up with the Biblical myth of the Leviathan and with giant squids.

“In the course of this process, lots of strange things happen. After almost 200 years, the Kraken becomes a squid. In Moby Dick it is a giant squid, and in German the word krake has become synonymous with squid”, explains van der Meeren.

Still many mysteries at sea

Although there aren’t any monsters in the ocean, there may still be big animals that we are yet to discover.

“We know so little about the ocean, and particularly about the deep sea. We have barely peeked through the keyhole. We are beginning to get good at using acoustics and underwater cameras, but there is still so much we don’t know”, says van der Meeren.

She is glad that the ocean is still full of mysteries.

“As researchers, we are curious and want answers, but we also need there to be unanswered questions. That’s why I’m thankful the ocean is an endless source of mysteries.”

The mystery of the missing squid eggs

One good example is the European flying squid Todarodes sagittatus, which has been harvested for 100 years.

“We have never seen its eggs or larvae anywhere in the world. We suspect that it creates a jellylike coating around its eggs, like many of its relatives do, but we have never found a single egg or larva”, says van der Meeren.

The balls of “jelly” that have been found by divers along the Norwegian coast in recent years come from a close relative: the southern, shortfin squid, also known as Illex coindetii.

“Until recently we didn’t even know that it was common along our coast”, concludes van der Meeren.