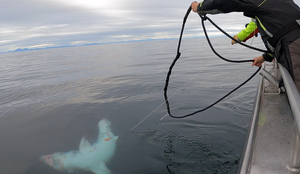

Tagging a furious shark

Powerful forces come into play when you want to tag a porbeagle shark. Porbeagles can reach up to three metres long and weigh 200 kilos.

Photo: Institute of Marine ResearchPublished: 20.09.2022 Updated: 10.10.2022

While marine scientist and tagging expert Keno Ferter was at a meeting to discuss how to best tag porbeagles, several boats that take tourists for fishing in Lofoten reported that they are frequently catching the shark.

– We jumped on the next plane to Lofoten, says Ferter.

The porbeagle is a fast swimmer and is in the same family as the feared great white shark. Found along most of the Norwegian coast and in other northern seas, it can reach over 3 metres in length and weigh more than 200 kg. This means it is around half as big as the great white shark, yet this is still an impressive size when you want to tag this individual from a small angling boat.

Powerful forces

Ferter and his colleagues have lots of experience of tagging various species of “marine megafauna”. He himself has tagged everything from saithe to bluefin tuna weighing hundreds of kilos, and helped to tag a mackerel shark in Australia as well as basking shark in Norway earlier this summer.

Watch the video: Tagging the second largest shark in the world

Nevertheless, Ferter was not prepared for what happened when it was the porbeagle’s turn.

– Incredibly powerful forces come into play. I’ve never experienced anything so strong, and we have tagged bluefin tuna that weigh hundreds of kilos. The experience was both frightening and exciting. The porbeagle has many sharp teeth, and you have to treat them with respect, says Ferter.

Challenging job

In order to tag a porbeagle, you first have to get it to bite, and then you have to manage to haul it in. That requires strong fishing rods, a strong fishing line, wire and a whole fish as bait. Thanks to invaluable help from experienced fishing guides at Nordic Sea Angling in Lofoten, after two days the researchers managed to catch a porbeagle and get it close to the boat.

But the hardest part of the job was still to come. How do you get an untamed shark weighing over 100 kilos to stay still long enough for you to attach the tag to its dorsal fin?

– Well, it is not easy! In order to keep the shark still we put a rope around its body, just in front of the dorsal fin, so that it lay up against the boat while we worked. The porbeagle we caught was around 2.5 metres long and weighed at least 100 kilos, says Keno Ferter.

– It put up a good fight, and it took some time for us to succeed by trial and error. Luckily, we got there in the end, and we are really happy to have demonstrated that it is possible to tag a porbeagle in Norwegian. We also lost another shark from the hook in the final step of the race, but we have learned a lot for next time we do this, says Ferter.

Each species of fish behaves in a completely different way, which means that the researchers have to adapt to their strategy.

– Bluefin tuna, for example, stay completely still provided we manage to get their head above water. The porbeagle, on the other hand, completely loses it if you do that, Ferter explains.

Sharks on the Move

The satellite tagging of a porbeagle and basking shark off Lofoten is part of the project “Sharks on the Move”, which is looking at migratory sharks like the porbeagle, basking shark and spurdog. The aim is to learn more about the current and future distribution of these three species in Norwegian waters, using methods including tagging experiments and data modelling.

– The Porbeagle is known for being highly mobile and capable of travelling thousands of kilometres across the whole Atlantic, but unfortunately we know too little about where they spend their time in Norwegian waters and how they migrate, says shark researcher and project manager Claudia Junge.

In half a year the satellite tag will pop up and “send home” data from the first tagged porbeagle (see fact box about the tags). The researchers are aiming to tag a higher number of porbeagles and basking sharks next year. Some of those tags will enable them to follow their migration in real-time.

We would like your help!

Four eyes see better than two, and the Institute of Marine Research would still really appreciate the help of the general public.

If you see a porbeagle, basking shark or anything else unusual in the ocean or along the coast, please report your observation to our portal Marine Citizen Science (“Dugnad for Havet”)!

By doing that, you help us to learn more about ecosystems and the marine environment. And perhaps some researchers are ready to jump on a plane in response.