Topic: Drones and new technology in marine research

The researchers are testing the Kongsberg sounder "Brage" in tandem with RV "Kristine Bonnevie" in search of sprats in the Hardangerfjord.

Photo: Christine Fagerbakke / IMRPublished: 20.10.2023 Updated: 25.10.2023

There is real need for drones in marine research.

As a result of climate change, ecosystems are changing rapidly. The ever-growing human footprint, particularly in the coastal zone, is another recognised concern.

In order to keep track of developments in fish stocks and other trends, researchers need more data, quickly.

Two main types of drones for marine research

Data must also be collected in a manner that is cost-efficient and environmentally friendly. This is where the drones come in.

There are two main kinds of uncrewed maritime vessels (drones):

AUV – autonomous underwater vehicle

… hover over the sea bottom collecting data on the topography, habitats and animals. At the Institute of Marine Research (IMR), we already use them for surveys like the Mareano project, which is mapping the Norwegian sea bed.

USV – uncrewed surface vehicle

… small, uncrewed boats equipped with the very latest scientific echo sounders and other sensors. These will initially be used by our researchers to map fish stocks, in the same way as – or to complement – the work they have traditionally done from ships.

The IMR has been a pioneer in carrying out experiments with its in-house kayak drone. It is capable of following a predetermined course, but it cannot see obstacles or dangers.

The IMR has also tested out other scientific USVs, such as the Saildrone and Sailbuoy.

Norwegian article with picture gallery on our kayak drone deployed in sprat monitoring:

Cannot take samples yet

The IMR has recently bought two AUVs and two USVs from Kongsberg Discovery. The AUVs have already entered service, and the USVs are due for delivery in the autumn. The latter, which have been developed in close cooperation with the IMR, have been given the name Sounder.

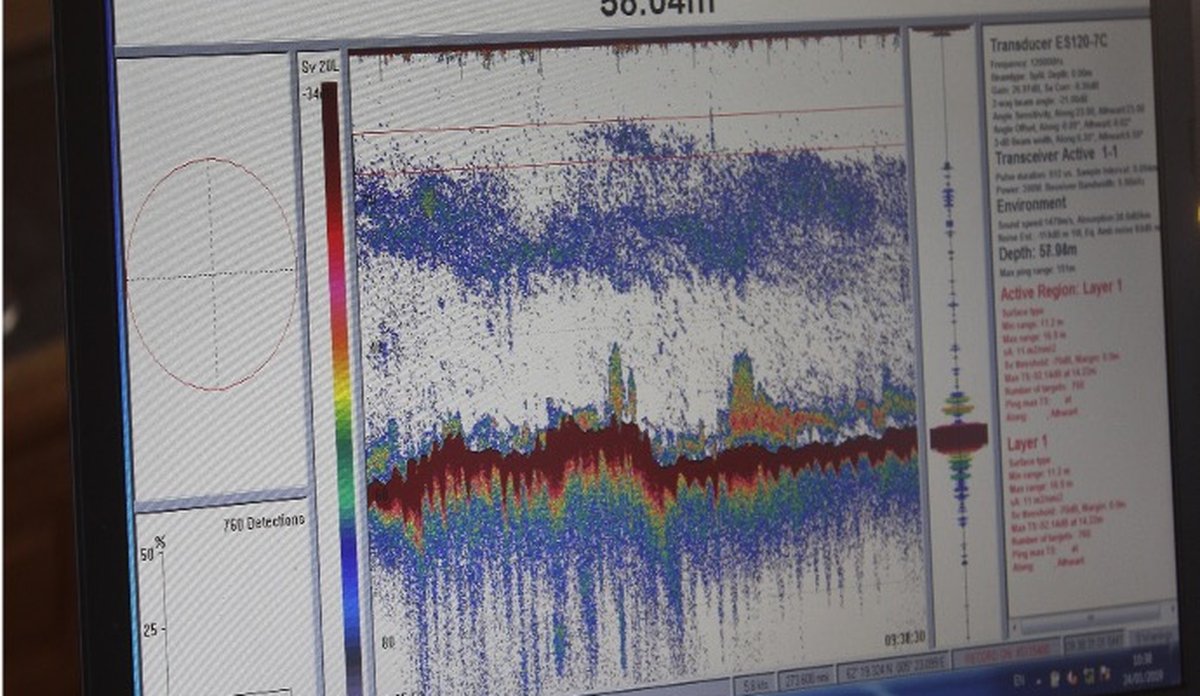

Echo sounders are the main tool researchers have to estimate the size and distribution of fish stocks in Norwegian waters. The researchers follow predetermined transects (paths on the map) and interpret what they see from aboard a research vessel.

In terms of its echo sounders, the Sounder is just as well-equipped as modern research vessels, but of course it cannot perform trawls and take biological samples of the fish. Scientists use these samples to confirm their interpretation of the echo sounder images, as well as to get an understanding of the age structure of the fish population. In other words, how many fish there are in each year class (“generation”).

Observing fish in new places

Since they cannot take samples, for the moment the drones act as a supplement to the research vessels.

However, if we give them appropriate tasks, they allow us to collect more data, more efficiently. It is also possible to imagine a closer partnership with the fishing industry on biological samples – for instance one inspired by the catch sampling lottery where fishers supply biological samples from their catch.

The drones can also get closer to animals without scaring them, and they can see fish in the upper few metres, just below the surface. That is a blind spot for research vessels, which have their echo sounders fitted to their keels.

During operation, the drones produce hardly any greenhouse gas emissions, or sound and light pollution, and they are cheap to operate.

Since full resolution echo sounder data are currently too big for the drones to transmit to base via satellite, the IMR is working to develop automated species identification and echo sounder interpretation through the project CRIMAC. In other words, eventually the drones may be able to interpret what they see themselves and send us a real-time “summary”. Researchers can then subsequently quality assure their interpretation, spurring further machine learning.

With a mother ship, with a “pilot” working from home, or completely independently

Initially, the IMR will use uncrewed vehicles together with, or deployed from, traditional research vessels in an “armada strategy”.

Over time, they will be set to operate more independently. How autonomously they can operate will also depend on the extent to which legislation allows the use of uncrewed vessels.

Some drones, such as the Sounder, can also be piloted from a remote control room.

The IMR also uses remote-controlled aircraft and off-the-shelf quadcopters (commonly referred to as “drones”) to photograph sea mammals, such as harbour seals along the coast. These images are used to count the seals, giving data for a stock estimate.