Topic: Sea spiders

Sea spiders are found in all of the oceans and at both poles.

Photo: Institute of Marine Research

Nymphon sp.

Photo: Erling Svensen / IMR

Sea spider with eggs.

Photo: Erling Svensen / IMRPublished: 08.05.2020 Updated: 25.02.2025

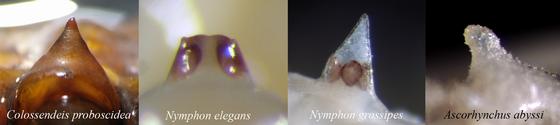

Sea spiders have four pairs of legs for walking, and their leg spans and body lengths vary greatly. A medium-sized sea spider may have a leg span of 5–7 cm, while the very largest species, such as the Colossendeis colossea, can have leg spans of 70 cm. The species are classified on the basis of characteristics such as their claws (chelifores), their proboscis (an elongated appendage with a mouth at the end of it) and their antennae (palps) (Figure 1). For example, some species have claws and antennae, whereas others don’t. Another characteristic trait of the sea spiders is their egg-carrying (ovigerous) legs. These are used by males to carry the eggs until they hatch. Even after hatching, juveniles sometimes remain close to the male until they are quite well developed.

On the front segment of their bodies, sea spiders have a protuberance (tubercle) with a few small eyes on top of it. The shape of this protuberance is often used to help determine the species (Figure 2). In some species the tubercle and eye is greatly reduced; this is typically true of species that live in the deep oceans.

Sea spiders are benthic animals, and can be found from the coastal zone down to very deep waters. Some species can also display pelagic behaviour. Sea spiders move slowly, so they feed on stationary or slow-moving animals. They eat anything from sea nettles, sponges and snails, to bristle worms and algae. Approximately 40 species of sea spider have previously been identified in Norwegian coastal waters. The MAREANO programme, which is also collecting species from the deep oceans, has so far found 21 species (May 2011). The map (Figure 3) shows where the species discussed below were found.

The Cilunculus battenae (Figure 4) was found at a depth of 388 m at one station (R421). This single specimen is the first of its kind to be found in the Norwegian economic zone. The species has previously been observed further south, on the Wyville-Thompson ridge (between the Faroe Islands and Shetland) and on the Cape Verde slope (West Africa), at depths of 690–1160 m. It was first described as recently as 1993, possibly because it is a small species that is easy to overlook: it’s body is only 1.5 mm long. Its claws are quite small, almost rudimentary (vestigial).

The Colossendeis proboscidea and C. angusta (Figure 5) are both large species, with the former having a leg span of up to 25 cm. The C. proboscidea has a relatively long proboscis, and its legs are close together near the body, which is how it can mostly easily be distinguished from C. angusta. The two species were found at seven and five stations respectively, with no more than three individuals at any given station. C. proboscidea is considered a northern species, and in the past it has been observed off eastern Finnmark. C. angusta has a wide geographical distribution, and is considered a bipolar species. It has been identified in the Atlantic, Pacific, Arctic and Indian oceans at depths of 150 to 5000 m. In the Arctic, where even the shallow waters are cold, it has been observed at depths of 12–18 m.

The Boreonymphon abyssorum, B. ossiansarsi and B. robustum (Figure 6) are spectacular, medium-sized sea spiders. Although they were mainly found at depths of 1,000–2,000 m, they were also observed in waters as shallow as 140 m. The most characteristic trait of these species is their large, curved claws. B. abyssorum is the most common Boreonymphon species in Arctic waters, and it was found at the largest number of stations in the material analysed after the MAREANO expeditions in 2007–2009. B. ossiansarsi and B. robustum were only found at one station each: R311 and R346 respectively.

50 individuals of the species Nymphon elegans (Figure 7) were recorded at R189 at a depth of approximately 900 m. The species has only once previously been reported in Norwegian coastal waters, in the Barents Sea near eastern Finnmark. In addition, it has been found in deeper waters in the Norwegian Sea by the researcher Georg Ossian Sars, in the eastern part of the Icelandic economic zone, in the Kara Sea, and just north of the Wyville-Thomson ridge. The N. elegans is a slender species, with long, narrow toothed claws. It can be distinguished from other species by the fact that one of the fingers of the claw is club-shaped, rather than pointed (Figure 1).

The Ascorhynchus abyssi (Figure 8) was described by G.O. Sars in 1877 in conjunction with the Norwegian expedition to the Arctic in 1876–1879. It belongs to the deep-water family Ascorhynchidae, and has previously been found at depths of 1500–4000 m in the Northeast Atlantic and in the Arctic. The species was found at two MAREANO stations (R487 and R488), at depths of 2,555 m and 2,117 m, where it was the dominant sea spider species. Both of the stations are situated in cold waters (below 0 °C), north-west of the Lofoten Islands. The Ascorhynchus abyssi is equipped with a large, downward-pointing proboscis. On its back, it has prominent protuberances on each segment. The protuberance on the front segment is a tubercle, but this species does not have any eyes (Figure 2), which can be explained by the fact that it lives in constant darkness in the deep oceans. The claws are also vestigial (Figure 1).

It is possible to distinguish between the Pseudopallene brevicollis and P. longicollis (Figure 9) by the different lengths of their “necks”. P. longicollis has an unusually long neck, whereas P. brevicollis has a short one. Apart from that, both species have compact, almost spherical claws with ganglia on the inside (Figure 1). A small number of Pseudopallene brevicollis individuals were found at four stations (R189, R346, R379, R416). One individual was previously reported along the Norwegian coast by G.O. Sars at the end of the 19th century, off the coast of eastern Finnmark. P. brevicollis is an Arctic species. It has previously been observed in the Kara Sea and Norwegian Sea.