Topic: Stinging jellyfish

The Lion’s mane jellyfish (Cyanea capillata) prefer cold water, but is most often observed during summer when their food supply is most plentiful.

Photo: Michael Poltermann / Institute of Marine Research

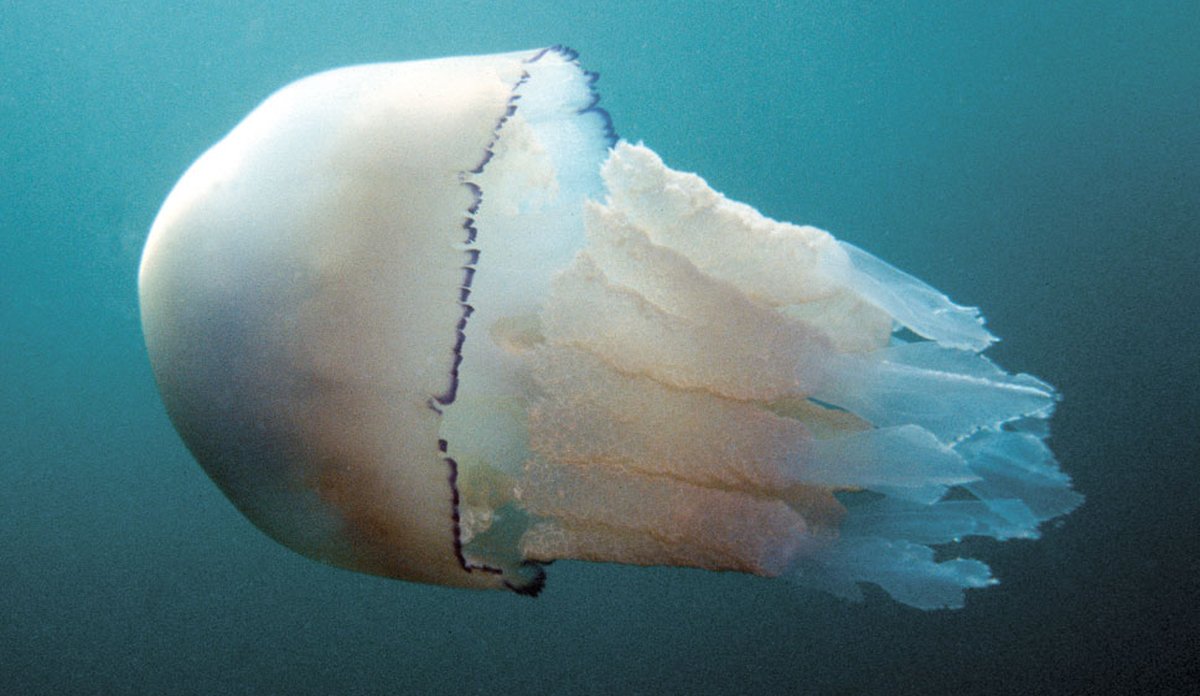

Cyanea capillata.

Photo: Erling Svensen / Havforskningsinstituttet

Blue jellyfish (Cyanea lamarckii).

Photo: Erling Svensen / IMRPublished: 30.03.2020 Updated: 27.07.2020

In Norwegian waters, two species of stinging jellyfish commonly occur. Of these, the lion’s mane jellyfish (Cyanea capillata) – the largest known species of jellyfish occurring in cold, boreal waters of the Arctic, northern Atlantic, and northern Pacific Oceans – is most common. While the blue jellyfish (or bluefire jellyfish) (Cyanea lamarckii) is rarer and has a more southern distribution and occurs mostly along the coast of southern and mid-Norway.

The blue jellyfish is distributed further south, and occurs along Norway’s southern and western coasts,while, the lion’s mane jellyfish is more of a cold-water species. It is reported that the stings from these two species are equally powerful. The moon jelly (Aurelia aurita) is a nearly translucent jellyfish that occurs in Norway; this species should not be confused with the blue jellyfish. They have short tentacles that usually do not sting humans, and their gonads (reproductive organs) are found in four distinctive rings on the surface of their mantle. Moon jellies may also be called: moon jellyfish; common jellyfish; or saucer jellies.

Drifting with the currents

Jellyfish are planktonic organisms and are largely at the mercy of the weather to determine where they will end up. They are able to swim, but do so to regulate their depth in the water column more so than to propel themselves forward. Since stinging jellyfish prefer low temperatures, they sink beneath the warm surface layers in summer. When they do appear in surface waters, they have likely been carried there by the currents; aggregations often become lodged inside the headlands or capes of bays and harbours.

People associate jellyfish with the summer sun. Although they prefer cold water, they are observed most often during summer when their food supply is most plentiful. Jellyfish are carnivores and eat crustacean plankton, other jellyfish, larval and juvenile fish, and whatever else gets caught in their tentacles.

Life cycle

Jellyfish are free-swimming gelatinous zooplankton species with specialized cells which they use mainly to capture prey. Cyanea capillata can reach up to two meters in diameter, and have tentacles up to 30 meters long. They have a relatively complex life cycle which includes both sexual and asexual phases. During summer, males release sperm that swim to females and fertilize eggs within their abdominal cavities. Here the larvae are hatched and eventually released as free-swimming individuals which then settle on the bottom and turn into small polyps that can remain there for many years. In spring the polyps begin to reproduce asexually and tiny jellyfish (ephyrae) develop and break off from the top of polyps. They are so small that they can only be viewed through a microscope. They grow quickly, however, and soon can be observed in large numbers as adults just before the end of their life cycle. These adults will die during the course of winter, while future generations dwell on the bottom in the form of polyps.

Ecosystem change

Change is apparent in the North Sea and along the coast of southern Norway. Kelp forests are disappearing, and many fish stocks and seabird populations are in decline. Some believe that numbers of jellyfish have increased in recent years, both here and in the Mediterranean Sea, but there is no scientific evidence that confirms this. Although jellyfish are recognized as important components of marine ecosystems, they are not commercially important species. Therefore, they are not prioritized and limited monitoring and research is conducted to learn more about them.

Be curious!

The next time you see a single jellyfish, or a hundred of them, let your fear give way to curiosity. Look into the water and be amazed by their elegant swimming motions, and how their tentacles live a life of their own. See how small fish manage to find protection between jellyfish tentacles without being stung, or how jellyfish manage to capture their prey. This is guaranteed to both thrill and delight!

Large jellyfish in Norwegian waters

Each year in Norway, lion’s mane jellyfish and moon jelly occur locally in large numbers. Blue jellyfish also occur regularly in southern Norway. Two other regularly observed species are the dustbin-lid jellyfish (Rhizostoma pulmo) and compass jellyfish (Chrysaora hysoscella). The dustbin-lid jellyfish can become so enormous that it may be difficult to get them into the boat if they get caught in the net. Yet another deep-water species occurring on Norway’s coast is the helmet jellyfish (Periphylla periphylla) that thrives in the deeper fjords. This species can occur in high densities, and comes to the surface at night. Its colour ranges from deep red to purple, and it has relatively thick tentacles.

Why jellyfish stings burn

Nematocysts (stinging cells) are positioned close together on the jellyfish tentacles. These cells contain a toxin that can paralyze or kill small prey such as plankton and fish larvae. Whenever a jellyfish comes in contact with another organism, nematocysts are instantly propelled out of the cell like an arrow to inject venom into the skin of the prey or the attacker. Moon jellies have weak venom; their sting is hardly noticeable by humans; while other species may have powerful stings. In warmer climates, the stings from some jellyfish species are so toxic that they are deadly for humans.

If you do get stung

If you do get stung by a jellyfish, rinse the affected area well with salt water, but do not rub your skin. Rubbing may cause nematocysts which did reach your skin, but have not yet fired, to become activated. There also are ointments available at pharmacies to minimize the pain. In rare cases, persons with allergies react so severely that medical attention should be sought.