Kelp to shield mussels from ocean acidification

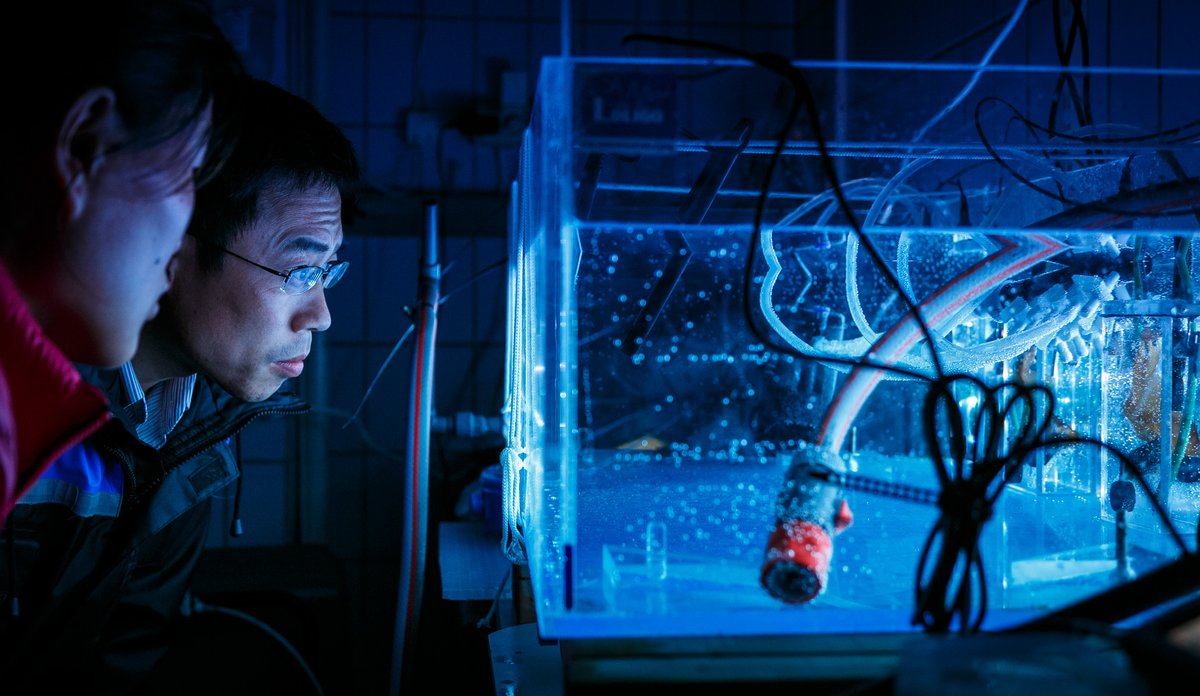

Professor Zengjie Jiang (right) and master student Xiao Jin Wang monitoring oxygen production in kelp under different light conditions and with varying quantities of mussels. (Photo: Erlend A. Lorentzen / Institute of Marine Research)

Published: 29.11.2017 Updated: 06.08.2021

“Ocean acidification is a problem for animals with shells. When pH levels drop, they struggle to form their shells. Shellfish are one of the most important farmed species in the world,” says marine biologist Samuel Rastrick at the IMR.

He is joined by his colleague Professor Zengjie Jiang and master student Xiao Jin Wang from China’s Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute. The Environment and Aquaculture Governance project has brought them to Austevoll.

Kelp and shellfish lead the way

Carbon dioxide is absorbed by the ocean, which turns it into carbonic acid. This process makes the seawater more acidic. The team of scientists wants to find out whether farmed kelp can help mussels.

“China produces two million tonnes of dry kelp every year. Kelp makes up 11 per cent of the mariculture production in China, while shellfish account for 72 per cent,” says Zengjie Jiang.

That makes China the biggest mariculture producer in the world, providing over half of the world’s total production. In comparison, Norway accounts for less than three per cent.

Can the species help each other?

Kelp farms extend for hundreds of kilometres along China’s coastline. Like other plants, kelp absorbs carbon dioxide in order to create sugar by photosynthesis.

“We are looking into whether kelp can remove enough CO2 locally to be able to protect mussels against the expected increase in ocean acidification. The mussels also produce nutrients that could benefit the kelp. It therefore makes sense to cultivate them together,” says Zengjie Jiang.

Integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) is a widespread and traditional practice in China. It uses waste products or environmental effects from one species to accommodate another. The practice is being trialled in Norway, too, but the currents, deep seas and seasonal variations are a challenge.

“Our experiment has yielded positive results, provided the kelp has access to light. We are now trying to work out the best balance between light and the quantity of kelp and mussels,” Samuel Rastrick explains.

From tanks in Austevoll to the Chinese seas

“In Austevoll IMR has state-of-the-art equipment for conducting in-depth physiological experiments. In China we can move the experiments to large-scale trials in the sea. The collaboration therefore benefits both parties,” he concludes.

The collaboration project between the IMR and the Yellow Sea FIsheries Research Institute recently organised a conference in China. Norwegian and Chinese scientists were in attendance in order to learn more about research and aquaculture management in the two countries. Samuel Rastrick and Jiang Zengjie presented the experiments taking place in Austevoll and in China.