Fjords create mercury problems

The mountains around the fjord funnel rainwater containing mercury into the fjord. Deep-sea fish in Sognefjorden contained almost as much mercury as fish from the industrial areas in Hardanger, even though there were no known sources of pollution.

Photo: Erlend A. Lorentzen / HavforskningsinstituttetPublished: 28.01.2019 Updated: 14.02.2019

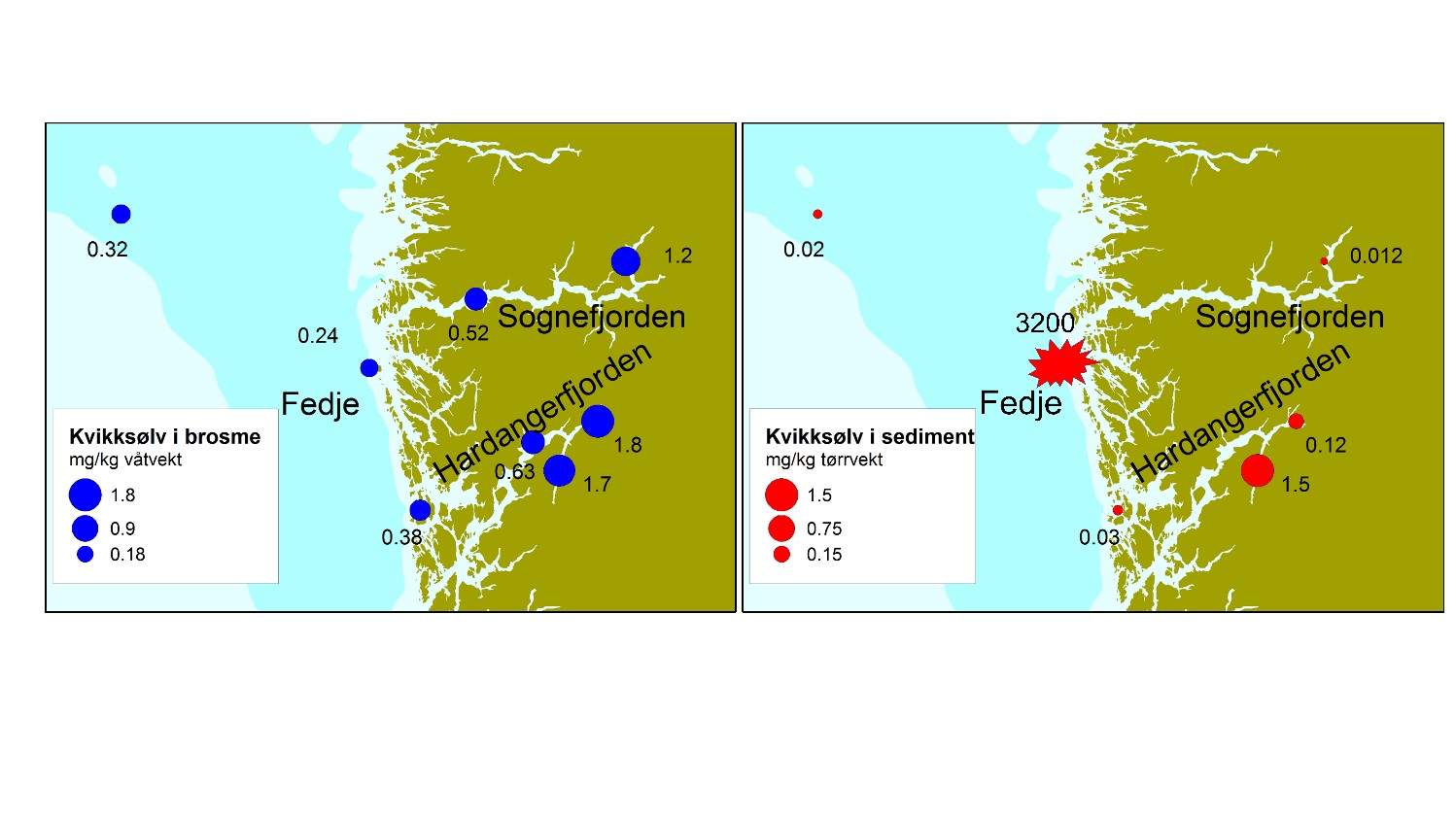

The scientists just couldn’t make sense of it. Deep-sea fish have high levels of mercury even in fjords where there haven’t been any industrial emissions or other known sources of mercury pollution. Meanwhile, the complete opposite is true of an open area such as off the Fedje archipelago in Hordaland. There the wreck of a World War II submarine has polluted the surrounding seabed with mercury, but nevertheless the fish in the area don’t contain much mercury.

Excessive levels of mercury, which is a highly toxic heavy metal, can affect brain function and development, particularly in young people. The Norwegian authorities therefore carefully monitor food to make sure that it doesn’t contain more than a safe level of mercury.

Mercury in clean fjords

Sørfjorden, which is a branch of Hardangerfjorden, has been polluted by heavy industry for more than a century, and heavy metals like lead, zinc, mercury and arsenic create problems for fish and other seafood in the area. Sediment samples from the seabed near the industrial area contained a hundred times more mercury than samples from the outer part of the fjord, and the authorities advise against eating tusk and blue ling from all of Hardangerfjorden, since these deep-sea fish contain very high levels of this harmful heavy metal.

More surprisingly, deep-sea fish in Sognefjorden contained almost as much mercury as fish from the industrial areas in Hardanger, even though there are no known sources of mercury pollution. In Sognefjorden, the average values at seven of eight locations sampled exceeded the threshold set by the authorities, and the Norwegian Food Safety Authority therefore advises against eating tusk from most of Sognefjorden.

Similarly, mercury levels in deep-sea fish in Eidfjord, a less polluted branch of Hardangerfjorden, were even higher than they were closer to the heavy industry, in spite of Eidfjord only having a tenth of the amount of mercury in its bottom sediments.

So why are heavy metal levels so high in fish in Sognefjorden and other fjords without heavy industry? The answer may lie in the fjord itself.

Fjords funnel toxins

Mercury travels long distances in the atmosphere, and mercury released from a coal-fired power station in China may be deposited in Norway or the Arctic. In many places, long-range transported pollution is therefore the biggest source of mercury in the environment.

A fjord surrounded by high mountains acts like a funnel, with large rivers transporting rainwater into the fjord from their drainage basins in the surrounding mountains. As a result, fresh water that ends up in fjords contains mercury from rainwater that has been collected in a large area and then carried into the fjord by rivers. In addition, the water in fjords isn’t exchanged as often as in the open ocean, so the heavy metals accumulate. This is supported by the fact that you find the highest mercury concentrations in fish from the innermost part of the fjords where the rivers flow into them.

Converted into dangerous methylmercury

The river water also carries large quantities of biological material from the land, providing good conditions for micro-organisms to convert the mercury into its most toxic form, known as methylmercury. This is the form of mercury that is most easily absorbed by mammals, birds, fish and people. It is also the major form of mercury (70-100%) in fish fillets.

In the open ocean, on the other hand, the mercury is less accessible to micro-organisms, so it isn’t converted into methylmercury at the same rate as fjords. That explains why the deep-sea fish around the submarine wreck at Fedje don’t contain particularly high levels of this harmful form of mercury, since mercury from the submarine is not bioavailable and in the open ocean the water can freely circulate.

The blue dots on the map show locations in Western Norway where mercury levels were measured in tusk. The red dots show locations where mercury levels were measured in bottom sediments. The maps show that there isn’t always a link between the amounts of mercury in the sediments and in the fish.