Researchers discovered leak from Komsomolets

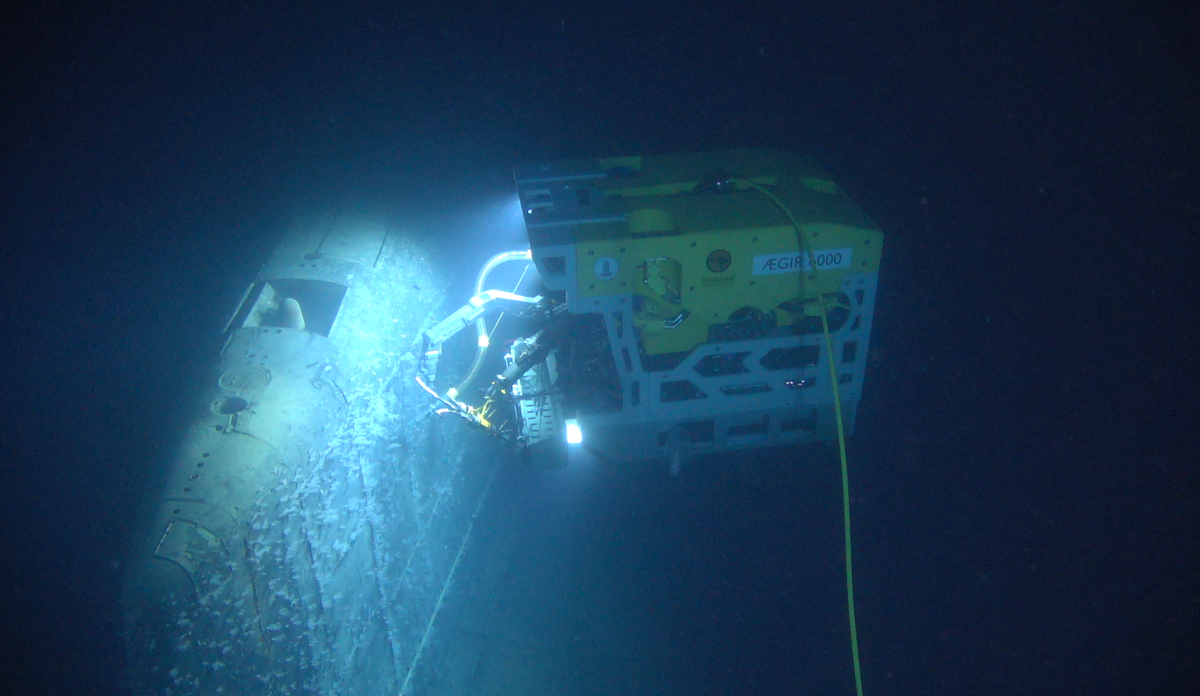

The ROV Ægir 6000 at work on the submarine wreck at a depth of almost 1,700 metres in the Norwegian Sea.

The ROV taking a water sample from the ventilation duct.

Is it on its way? Andrey Volynkin of the IMR waits expectantly for Ægir to emerge from the depths.

Photo: Stine Hommedal/HI

On its way up to the surface, bearing water samples.

Photo: Stine Hommedal/HI

Before the water samples can be unloaded, the scientists check whether the ROV has been contaminated by coming into close contact with Komsomolets.

Photo: Stine Hommedal/HI

Andrey Volynkin (IMR) and Justin Gwynn (DSA) carefully investigate Ægir 6000.

Photo: Stine Hommedal/HI

Water samples ahoy! Straight from the deck and into the lab.

Photo: Stine Hommedal/HI

Inside the lab, the samples must be handled carefully.

Photo: Stine Hommedal/HI

The sample beakers are filled with seawater and attached to a detector that can measure any radioactivity.

Photo: Stine Hommedal/HI

The ROV has allowed the scientists to take more precise samples from the nuclear submarine than ever before. Louise Kiel Jensen of the DSA is looking forward to analysing the living organisms that Ægir 6000 has collected from the wreck itself.

Photo: Stine Hommedal/HIPublished: 10.07.2019 Updated: 06.08.2021

Several samples taken in and around a ventilation duct on the wreck of the submarine contained far higher levels of radioactive caesium than you would normally find in the Norwegian Sea.

The highest level measured in a sample was 800,000 times higher than normal.

However, other samples from the same duct did not contain elevated values.

Leaks from the duct have been documented previously

“We took water samples from inside this particular duct because the Russians had documented leaks here both in the 1990s and more recently in 2007”, says the expedition leader Hilde Elise Heldal.

“So we weren’t surprised to find elevated levels here.”

The levels of radioactive cesium-137 the researchers found in the samples were up to 800 Bq per litre, as opposed to around 0.001 Bq per litre elsewhere in the Norwegian Sea.

Not alarmingly high

Although that sounds like a lot, Heldal emphasises that the levels aren’t dangerously high.

She puts them into perspective by citing the permitted limit for radioactive caesium in food products:

“After the Chernobyl accident in 1986, Norwegian authorities set this limit to 600 Bq/kg”, says Heldal.

“The levels we detected were clearly above what is normal in the oceans, but they weren’t alarmingly high”, explains the expedition leader.

“Over the past few days we have also taken samples a few metres above the duct. We didn’t find any measurable levels of radioactive caesium there, unlike in the duct itself”, says Justin Gwynn, a researcher at the Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority (DSA).

Interesting “cloud” may show site of leak

Just before taking the first sample that gave an elevated reading, researchers noticed a kind of “cloud” rising up from the duct.

A “cloud” was also seen rising from a grille nearby, where the researchers again measured elevated levels.

The big question is whether this “cloud” may be related to the radioactivity the researchers observed inside the duct.

“It looks very dramatic on video, and it’s definitely interesting, but we don’t really know what we’re seeing and why this phenomenon occurs. It’s something we want to find out more about”, says Justin Gwynn of the DSA.

Located the submarine at the first attempt

The research vessel G.O. Sars reached the area where the wreck was thought to be on Sunday evening.

Information about the exact position of the wreck varies slightly, so the researchers were quite excited to see how quickly the ROV Ægir 6000 would find Komsomolets.

In the event, Ægir 6000 managed to locate the wreck on its first dive. The scientists could then observe the state of the wreck with their own eyes, in real time.

Most thorough investigation ever

The Institute of Marine Research (IMR) and DSA have performed joint annual surveys of the wreck since the 1990s.

Each year they have taken seawater and sediment samples, but without being able to “see” the wreck.

Their most recent pictures of it had been taken by a Russian expedition twelve years ago.

This year’s survey is the most thorough investigation of Komsomolets ever performed by Norwegian scientists.

“We have been wanting to do a survey with an ROV for a number of years. Ægir 6000 allows us to see exactly where we are taking samples around the wreck, and equally importantly we’ve been able to use its cameras to zoom in and study the whole nuclear submarine section by section”, says Heldal.

Samples of seawater, sediment and organisms

The researchers have taken samples of seawater, sediments and organisms that have set up home on the wreck itself.

The freezers and refrigerators on G.O. Sars are now full of samples that will be further analysed later.

In other words, we only have the preliminary results so far.

“We will study the samples even more thoroughly when we get home”, says Heldal.

No big impact on Norwegian seafood

“What we have found during our survey has very little impact on Norwegian fish and seafood. In general, caesium levels in the Norwegian Sea are very low, and as the wreck is so deep, the pollution from Komsomolets is quickly diluted”, explains Heldal.

The IMR has previously modelled what would happen if all of the radioactive caesium in the wreck were to leak out at once.

The conclusion was that the impact on fish in the Barents Sea would be negligible. There is not much fish in the area where Komsomolets is located.

"This is one of several cruises the Institute of Marine Research regularly undertakes to monitor the environmental state of the oceans - this time with the top notch technological equipment in the form of the ROV "Ægir 6000". We have comprehensive programs in place to monitor environmental status and marine resources in the North Atlantic. We can follow any changes and influences in everything from large ocean systems to the seafood being served on our dinner tables. It is reassuring that the findings from this cruise do not seem to represent any danger for Norwegian seafood", says Sissel Rogne, director at the Institute of Marine Research.

Important to continue monitoring

Both the IMR and DSA still believe that it is vital to continue monitoring the only known source of radioactive pollution in Norwegian waters.

“We need good documentation of pollution levels in seawater, seabed sediments and, of course, fish and seafood. So we’ll continue monitoring both Komsomolets in particular and Norwegian waters in general”, concludes expedition leader Hilde Elise Heldal.

As well as scientists from the IMR and DSA, researchers from the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU)/Centre for Environmental Radioactivity (CERAD) and Research and Production Association Typhoon (RPA Typhoon) have taken part in the survey, which will end in Tromsø on Wednesday, 10 July.