Sharks on the Move: Norwegian scientists tagged four 2.5m porbeagles in Lofoten

Published: 30.08.2023 Updated: 25.10.2023

For the media: Download video and photos from the porbeagle expedition here

From a small platform at the very back of the boat, marine scientists Keno Ferter and Otte Bjelland scan the horizon.

After many months of preparation, they are finally out at sea off the Vesterålen archipelago. The beautiful weather and recent porbeagle sightings in the area mean their expectations are high.

The marine scientists are accompanied by Harald Knotten, an inspector at the Directorate of Fisheries’ Sea Surveillance Service. Using a powerful fishing rod, he slowly reels in the line from a depth of 40 metres.

Suddenly the summer idyll is interrupted by a powerful tug on the rod. Could it be a shark?

“Then all hell breaks loose”

This year’s porbeagle expedition began in early August, in bad weather conditions. The first days on board the Sea Surveillance Service’s boat Rind were spent safely in port. But while the wind was blowing, the researchers prepared for what was ahead of them. And soon they were able to embark on their search for sharks.

Learn more: Shark Summer 2023

“We soon notice whether it is a shark. Long before we see it. First the line becomes heavy and still. As if it was caught firmly in the sea bed. After that, you might say that all hell breaks loose”, says Ferter.

Powerful forces are at play when you’ve hooked a 2.5 metre-long shark weighing well over 100 kg. First you must manoeuvre the shark up to the surface and then bring it right up against the boat. There it must be kept still while the satellite tags are attached to its dorsal fin.

No room for error

The shark team has a special technique for getting the shark up from depth and alongside the boat, to put them in a good position to tag the shark efficiently and without causing it any harm.

“There are lot of things you need to do in order to carry out the tagging in a way that is safe, both for the shark and for us on the boat. Safety is our top priority, and there is no room for error. We need seamless cooperation, good communication and experienced people in our team”, explains Ferter.

Learn more: Found first satellite tag from basking shark tagged last year

While Knotten reels in a resistant porbeagle, Ferter prepares for the tagging. All the necessary equipment must be prepared and placed within easy reach. It is important for the tagging process to be as quick as possible.

“It generally takes half an hour from when we hook a porbeagle to when we are ready to tag it. When the shark reaches the surface, the boat is still under power, and we are careful to keep a safe distance to the shark initially. When we get it closer, we turn off the propeller, to avoid any risk of the blades injuring the shark”, says Ferter.

Careful handling

In order to keep the shark still while it is being tagged, Otte Bjelland puts one rope around its tail and another around its abdomen. The one around the abdomen goes behind the pectoral fins and in front of the dorsal fin to hold it in place.

“We need two people to hold the shark firmly while it is tagged. It is hard work, but we have found a way to do it. We attach the tag to the shark’s dorsal fin through the cartilage. Once the geolocation tag is properly attached, we put on the archival tag. We also measure the length of the shark”, says Ferter.

In order to ensure that the shark gets enough water through its gills while it is alongside the boat, the boat moves sideways. This is done using the thrusters built into the bow and stern of the boat, so that it is safe for the shark.

Need to keep a cool head

Both the shark’s welfare and the safety of everyone working on the ship is top priority.

“As well as using specialist gloves, we have both a knife and pliers handy in case someone gets caught up in the fishing line or wire. Above all, you need to keep a cool head and have clear task distribution when carrying out the tagging”, explains Ferter.

Invaluable help from the general public

Tagging sharks is a team effort, and many people have contributed to this summer being a big success for the scientists.

At times, the shark hotline launched by the Institute of Marine Research before the summer has received lots of calls, and tip-offs from people who have seen basking sharks or porbeagles are worth their weight in gold to the tagging team.

“The help of the general public is invaluable to us. By giving us tip-offs during the summer, you have helped us to tag far more sharks than we expected. “

“We also have excellent assistants with us when we are out at sea. For the second year in a row, fishing guides from Nordic Sea Angling in Lofoten and Vesterålen have led us to the right fishing spots. They also help with the fishing as volunteers, and they actually caught one of the four porbeagles that we tagged, so they have made a fantastic effort for us”, says Ferter.

Shark hotline will stay open

This year’s porbeagle expedition is over, but the researchers do not rule out tagging more porbeagles over the autumn.

“The shark hotline will stay open, and you can leave a voice message if we don’t answer straight away. So, if we get the opportunity and the conditions are right, we don’t rule out suddenly tagging our fifth and sixth porbeagle”, smiles Ferter.

Unique data

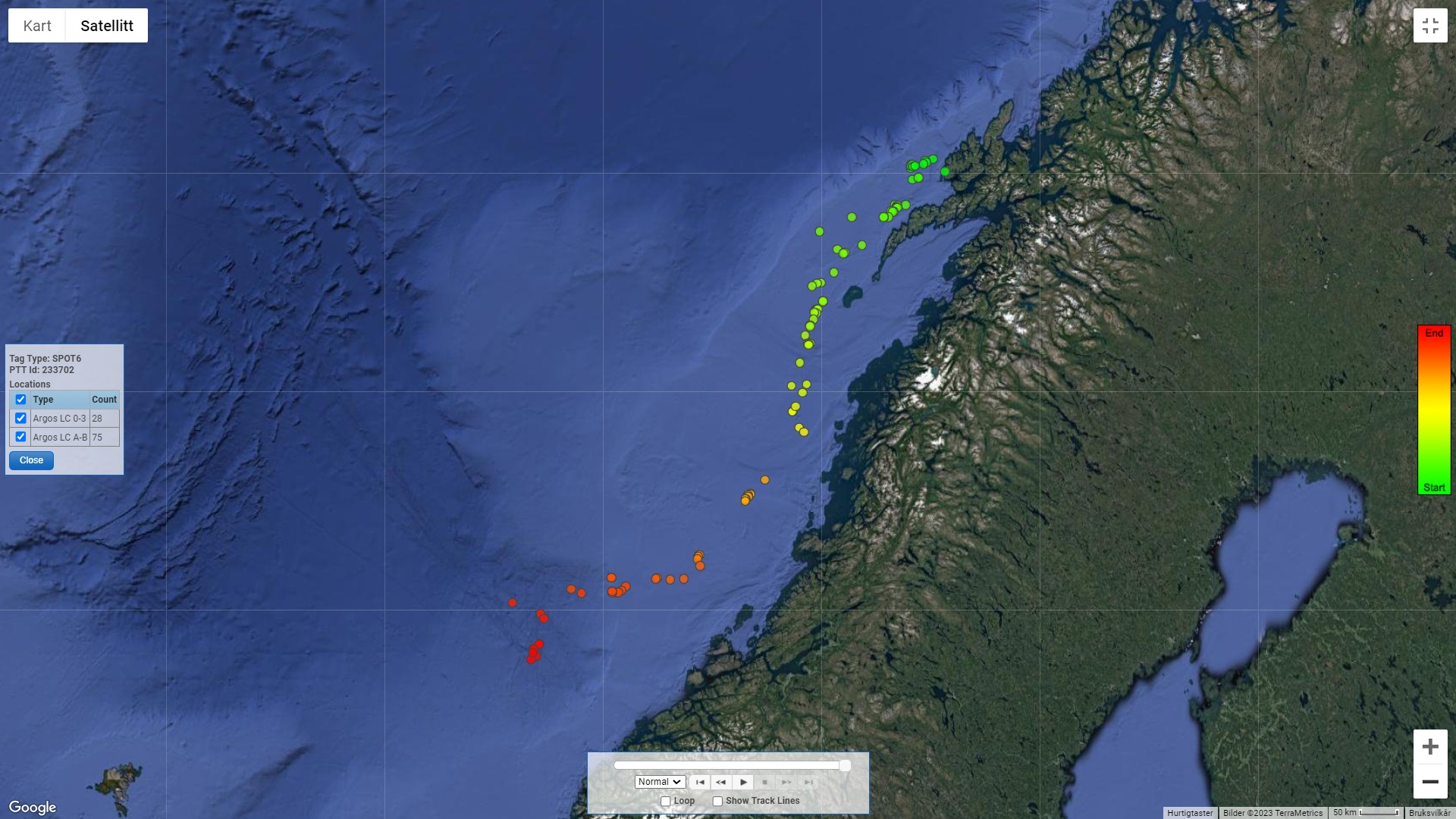

This is the first time that a porbeagle has been tagged with both archival and geolocation tags in Norwegian waters. The geolocation tags allow researchers to track the sharks in near-real time as long as they are at the surface, while the archival tags log data relating to depth, temperature and light.

“The porbeagle is an important predator, and we need more information about large predators in order to understand the whole food web and ecosystem in the ocean”, explains marine scientist Claudia Junge, who is managing the project “Sharks on the Move”.

The data will be used in the project “Sharks on the Move”, which is studying shark migrations and how they overlap with human activities.

“The tags will provide us with valuable information about where sharks migrate and how they use their habitat, both in Norwegian waters and beyond. More knowledge about sharks is in high demand both in Norway and internationally, and it provides a basis for sustainable management of populations” says Junge.