Porbeagle Shark swam from Lofoten in Norway to Canary Islands

Published: 29.04.2024 Updated: 30.04.2024

Like many people living in the north of Norway, a shark tagged by the Institute of Marine Research, set its course straight for warmer climates as the autumn cold set in.

With speeds of up to 100 kilometers per day, the porbeagle swam more or less directly from Lofoten/Vesterålen towards the Canary Islands.

"It's simply fascinating to see how quickly the shark moves, and very exciting to be able to show results from the tagging we have carried out," says shark researcher Claudia Junge, who leads the research project Sharks on the Move.

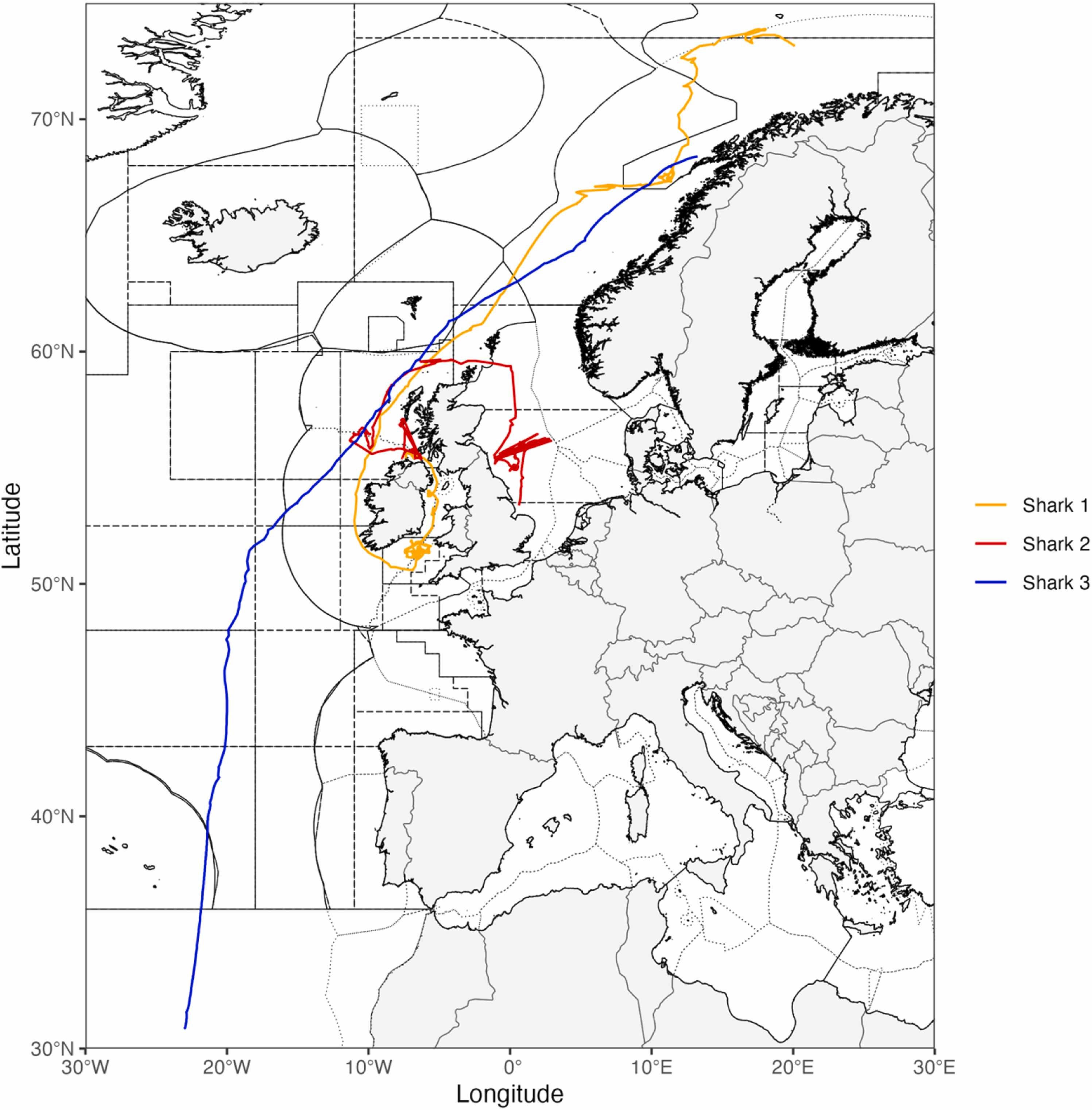

In a new scientific article, the migration patterns of three porbeagles are revealed, all of which were tagged during 2022.

"We tagged one of them off the coast of Lofoten/Vesterålen in August. The other two were tagged by Irish colleagues off the coast of Ireland in April the same year."

Read more: Tagging a furious shark

Researcher and shark met on holiday

Marine researcher and tagging expert Keno Ferter, who leads the tagging work on basking sharks and porbeagles, happened to be on vacation in the same area where the satellite tag detached and floated to the surface.

"I was lying on the beach in the sun when I got a message that the tag from the shark had come loose and started signaling. Four months earlier, I tagged the shark in Norway, and now we were suddenly both far south in the Canary Islands. It was absolutely wild," Ferter recounts.

The tag was a little too far away for the vacationing researcher to retrieve it, but he admits that the temptation to jump on the nearest boat was strong.

"Even though we get better data if the tag is recovered, it still sends signals when it's at the surface. We still get a lot of information, so we've had plenty to work with," says Ferter.

Swam in Different Directions

The three porbeagles have crossed several jurisdictions, national, and physical boundaries during the 4-12 months they were tracked.

"What the three tagged sharks have in common is that they migrate long distances and move fast. But they differed a lot in terms of where they were headed," Junge explains.

"One of the sharks tagged in Ireland stayed mostly in Irish and British waters. The other one swam all the way from Ireland up to the Barents Sea before taking more or less the same route to the Canary Islands as the shark we tagged in Norway. Later, it swam back north again."

Important International Collaboration

Porbeagle is considered a vulnerable species globally and was even worse off in the Northeast Atlantic (NEA), however, now it looks like this population is "on the road to recovery".

Last year, new catch recommendations for porbeagle were issued for the first time since 2009. The new recommendation allows for the landing of bycatch of the species up to a certain amount in the Northeast Atlantic.

"The porbeagle's long and rapid migrations underscore the importance of international collaboration across borders, sharing knowledge and enabling sustainable fishery and management of porbeagle," says Junge.

Les mer: Haisommeren 2023

Tagged Four Porbeagles in 2023

The researchers have even more data on porbeagle migrations to work with in the future. In August 2023, the tagging team from IMR succeeded in tagging four more porbeagles off the coast of Lofoten/Vesterålen. These sharks are tagged with both satellite archival and tracking tags.

"This will give us knowledge about how the porbeagle moves geographically in real-time because we can follow them on their journey. When the satellite tags come loose, we also get depth knowledge, quite literally, and find out more about how they move within the water column along the way," Ferter explains.

"We are receiving data from the 2023 sharks continuously, and it will be exciting to find out if those Norwegian sharks behave as differently as the sharks in this study," concludes Junge.

Video: scientists tagged four 2.5m porbeagles in Lofoten

Referance:

J.R. Bortoluzzi, G.E. McNicholas, A.L. Jackson, C. A. Klöcker, K. Ferter, C. Junge, O. Bjelland, A. Barnett, A.J. Gallagher, N. Hammerschlag, W.K. Roche, N.L. Payne,

Transboundary movements of porbeagle sharks support need for continued cooperative research and management approaches, Fisheries Research, 2024. Lenke: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2024.107007