This temperature provides perfect growth conditions for sea vomit

The Sea vomit was first discovered in Norway in December 2020 near Stavanger.

Photo: Rudolf Svensen / IMRPublished: 15.01.2025 Updated: 22.01.2025

Sea vomit (Didemnum vexillum) grows rapidly in several parts of the world, and the spread of the invasive sea squirt seems to be closely linked to temperature variations. But how do temperatures affect its growth here in Norway?

“We clearly see a very rapid growth and development of colonies in Norway,” says marine scientist Erwann Legrand.

However, the situation is a bit different here compared to the rest of the world. High or extremely low temperatures that affect colonies globally do not occur along the Norwegian coast.

Invaluable help from divers

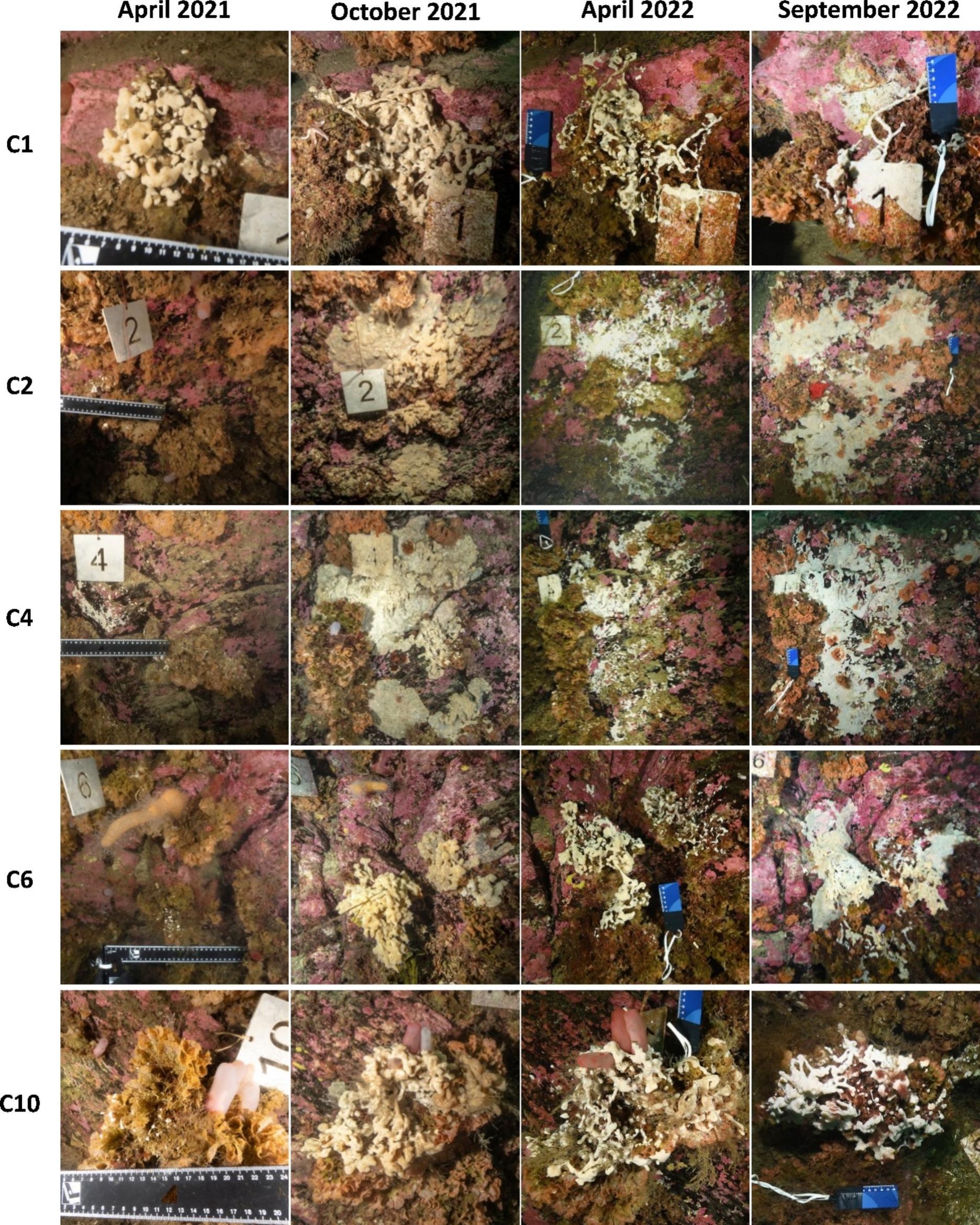

Divers from Stavanger have followed eleven colonies of sea vomit for two years, month by month. They have photographed and documented the size of the colonies and shared the extensive data with marine scientists.

By linking the photos to temperature data, scientists have now gained even better insight into why sea vomit spreads so quickly along the coast.

“The divers have done an invaluable job. Without their efforts, we could not have said so much about the growth rate of sea vomit,” says Legrand.

“The way they have worked is optimal for the research. I have only analysed and summarized what they have documented,” he adds.

Perfect growth conditions in Norway

Data from the Mediterranean, New Zealand, and Canada show that sea vomit stops growing or starts to die when it gets too hot or cold. This does not happen in Norway, because the temperature here remains stable year-round. However, the results from the experiment show that sea vomit stops growing when the water is below 8 degrees.

“Sea temperatures along the Norwegian coast are optimal for the growth of sea vomit,” explains Legrand.

Sea vomit thrives best when the seawater is between 13 °C and 18 °C. Along the coast, the temperature never exceeds 18 °C, and even in winter, it rarely falls below three degrees.

“We see that sea vomit shrinks a bit in winter, but not enough. It simply does not get cold enough, not even in Troms,” he adds.

Spreading northward

The photos show that sea vomit has also started to colonize kelp blades in some areas, which worries the scientist.

“When sea vomit colonizes kelp, it can inhibit photosynthesis. This will in turn affect the growth of the kelp,” explains Legrand.

“If the kelp cannot produce enough energy for the next season, it can increase mortality in the kelp forest. This affects not only the kelp but also all the species that depend on it.”

Sea vomit was discovered in Norway in 2020 and has already established itself in several places, especially in busy harbours. The rapid spread of the sea squirt is causing concern, especially because the species can continue to spread to higher latitudes.