Topic: String jellyfish

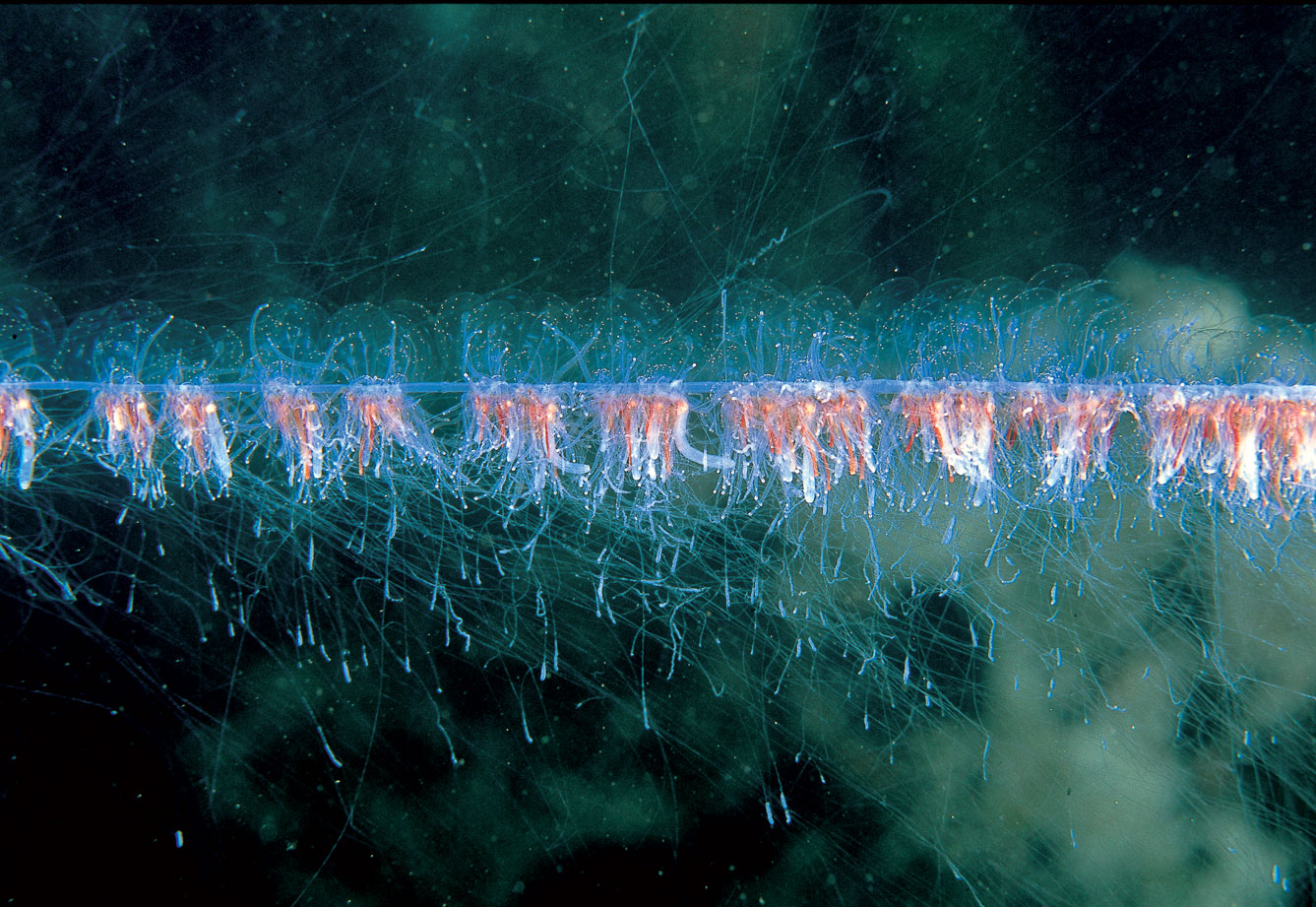

Apolemia uvaria under water

Photo: Erling Svensen / Institute of Marine Research

This colonial jellyfish can reach lengths of up to 30 metres.

Photo: Erling Svensen / IMR

The string jellyfish is an Atlantic species, and the researchers believe that it comes to the coast with inflows of Atlantic waters.

Photo: Erling Svensen / IMRPublished: 20.11.2023 Updated: 25.02.2025

String jellyfish form long chains that can reach over 30 meters in length and inhabit ocean waters ranging from the surface down to 1000 meters. Although widespread, in coastal waters String jellyfish are often found in the surface layers, and usually broken into smaller fragments of 10 m or less. String jellies naturally occur along the entire Norwegian coast, at highest densities in the autumn. Though there is some variability, String jellyfish can have strong venom which causes severe damage to affected fish.

Which species?

Globally, there are five described species within the genus Apolemia. In Norwegian waters, it has been documented that there is only one species, probably Apolemia uvaria. However, there is a need to revise the taxonomy of Apolemia, and Norwegian colonies should be compared with colonies from other ocean areas before it can be determined with certainty which species occurs here.

Biology

String jellyfish are colonial animals in the order Siphonophora. Each colony consists of many specialized individuals living as a kind of “superorganism”. Individuals (zooids) are connected to each other by a central “stem” and have different functions – for example, feeding, defense, reproduction, movement, or buoyancy.

The colony is divided into two regions: The uppermost region of the colony is called the nectosome comprising a gas-filled bladder (pneumatophore) which provides buoyancy and numerous swimming bells (nectophores), which provide propulsion. The region below the nectosome is called the siphosome, which is the longest part of the colony and contains feeding individuals (gastrozoids), translucent and red palpons for defense, bracts for protection, reproductive individuals (gonozooids) and tentacles. The individuals on the siphosome are arranged in a succession of groups, called cormidia.

When Apolemia is disturbed, the colony retracts using muscles on one side of the stem, which gives the colony a spiral or “zigzag” shape. In Norwegian waters the upper portion of the colonies (nectosome) with the swimming bells and pneumatophore are typically missing. This makes species identification difficult, since the original taxonomic descriptions are usually based on the morphology of the swimming bells.

Life cycle

Apolemia are dioecious, meaning each colony is either male or female, and can reproduce both sexually and asexually. In sexual reproduction, gametes are produced by the gonozooids and released directly into the water. Each fertilized egg then develops into a new colony by cloning. The asexual reproduction takes place in a budding zone on the stem, where the various zooid types are formed by asexual budding. This means that all individuals in an Apolemia colony are genetically identical but look different and perform different tasks. How individuals communicate and coordinate their tasks with each other remains an unsolved mystery. The entire life cycle takes place in the open water, with no benthic stages.

Food

Siphonophores are predators, and their prey is paralyzed and captured using stinging cells that contain venom. Apolemia has strong venom capable of killing relatively large prey. Apolemia diets can consist of crustaceans (copepods, krill, shrimp), fish, and other gelatinous plankton.

Where do String jellyfish come from?

There are many open questions related to string jellyfish, and the cause of mass occurrences is not known. Previous blooms of Apolemia in Norwegian coastal areas (1997, 2001, and 2021–2023) occurred late in the autumn, October–December. The jellyfish drift with ocean currents, and one theory is that they are transported towards the Norwegian coast with Atlantic water masses. Another possibility is that coastal blooms are linked to upwelling of deep water outside the shelf. We don’t currently know where the species reproduces or under what environmental conditions. The colonies drifting towards the Norwegian coast lack the uppermost part of the colony with swimming bells. This indicates that the colonies are in a late stage of their life cycle and dying when they reach the Norwegian coast. It is therefore assumed that the species does not have local production in Norwegian waters but rather is transported from external ocean areas by currents.

Implications for Fish Welfare

String jellyfish are not considered dangerous to humans, although it will sting if touched, however they can be extremely harmful to fish. Three times string jellyfish have led to increased mortality in fish farms: in 1997, 2001, and 2023. String jellies are broken into smaller pieces by waves or obstacles, and as a result can easily pass through nets. In 1997, a total of 10–12 tons of salmon died at two facilities in Øygarden and Fedje, while an unknown number of tons were emergency slaughtered. In 2001, 600 tons of fish died, including 400 tons in Trøndelag alone.

In the autumn of 2023, there was again a mass occurrence of string jellyfish along the Norwegian coast, affecting many fish farms. According to the Institute of Marine Research’s risk report for Norwegian fish farming, approximately 3 million fish likely died or were emergency slaughtered as a result of string jellyfish related injuries.

One of the affected farms in 2023 was the Institute of Marine Research’s sea facility in Austevoll, where we had to euthanize fish in multiple pens for animal welfare reasons. The fish from Austevoll were characterized by burn marks on their heads, backs, and fins. The injuries were most visible in the water. After the jellyfish encounter, many fish lay vertically against the net wall in the pen, and had obvious difficulty maintaining equilibrium. It is unclear which injuries are a direct result of the jellyfish, and which are an indirect result of abnormal behaviour triggered by the jellyfish.

Mortality was highest immediately after the string jellyfish influx to the farm, but remained elevated in the days and weeks following the incursion, even in the cages which initially appeared to have been only mildly affected. The autumnal timing of string jellyfish blooms is particularly challenging, as injuries to salmon in cold temperatures heal slowly and provide an entry point for secondary bacterial infections.

Mitigation measures?

Currently, little can be done to mitigate the impact of a string jellyfish incursion on fish farms. On a basic level, ensuring that dissolved oxygen saturations is as close to 100 % as possible will allow the fish to devote maximum energetic resources to healing and survival. In the event of a mass influx, feeding can be discontinued until the threat has passed so that the fish do not need to direct resources to digestion. Handling should be minimized, and before any bathing or transfer is undertaken it is important to make sure that the water is free of string jellyfish. Similarly, nets should be checked prior to cleaning and if string jellyfish are present postponed until jellyfish numbers are reduced.

Physical barriers around cages can significantly reduce the amount of string jellyfish the fish encounter, but must be considered in the context of local oxygen availability and fish health. Electrical stimulation has also been shown to trigger string jellyfish nematocysts in lab tests, but practical efficacy in the marine environment has yet to be tested. Similarly, several other protection methods are currently being examined in the FHF funded JellySafe project.